Albert Russ - Mineral Photographer Interview

Albert is a mineral photographer and a serious mineral collector from Slovakia. So far he managed to self-publish two books but he claims there is more to come in the future. You can enjoy his photos in most of the major mineral magazines. We will dive deeper into mineral photography and collecting in this interview.

Albert was born in 1978 in Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia, where he currently lives. He is an analytical chemist and still enjoys working in his field but also does professional mineral photography. You can see Albert's mineral photos in all of the important mineral magazines like Lapis, Mineralogical Record, Rocks & Minerals or Mineralogical Almanac. He self published books "Štiavnica Mountains" (2012) and "Ice Metamorphosis" (2018) and is now working on his third self-published book. Albert also participated on numerous other books and special publications including the most recent book on Slovak minerals "The Flowers of the Mines" (2020).

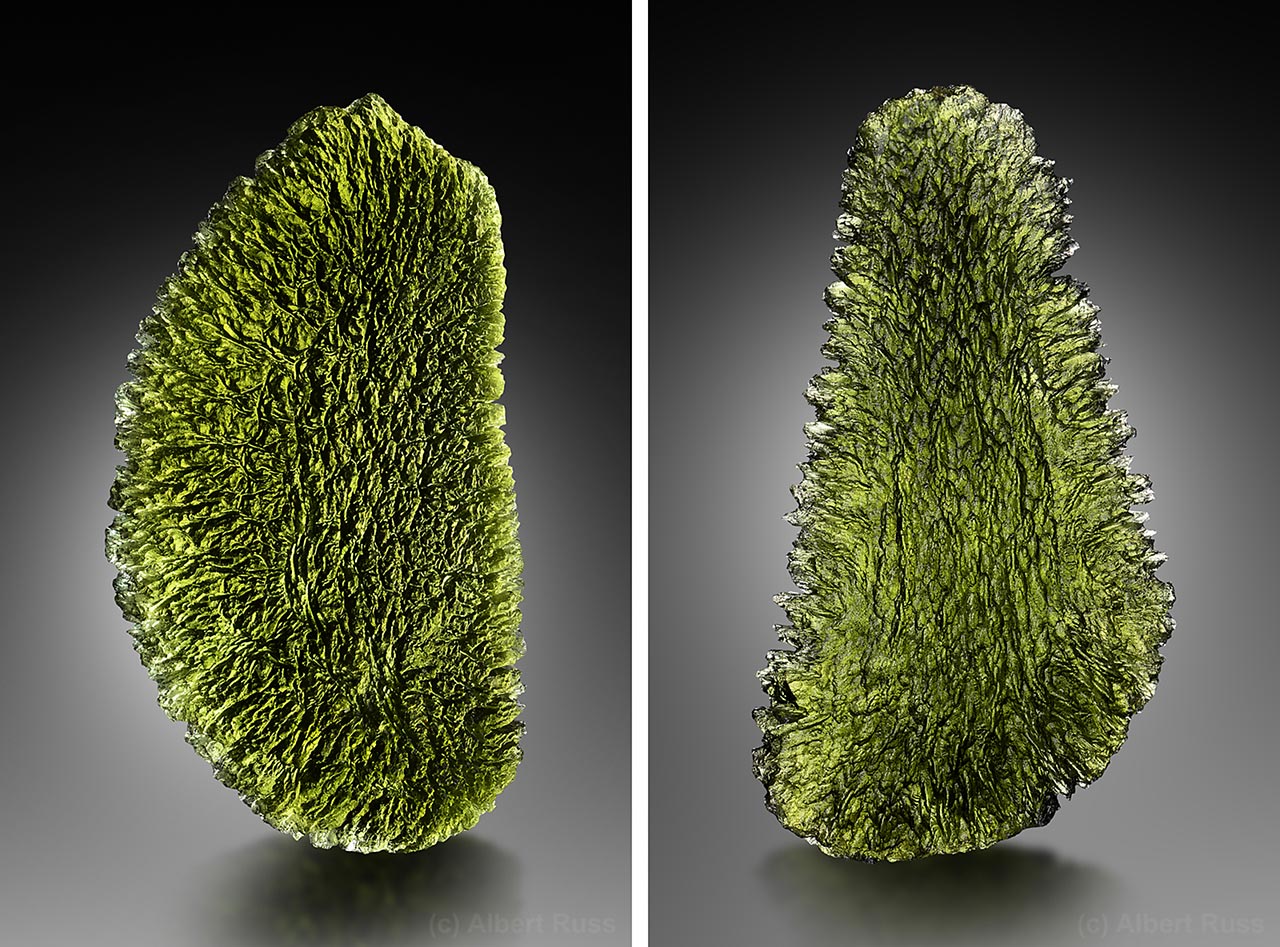

Besides being a mineral photographer, Albert is also an avid mineral collector, specializing in quartz, especially amethyst from worldwide locations.

Except being a (mineral) photographer, you are also a mineral collector. Can we start with some information about your collection?

I started as a mineral collector very long time ago. As a little boy I had interest in minerals as curious objects of various shapes that sparkled. In 1986 I was in Banská Štiavnica with my father. My first specimens in my collection are from that trip. Later I focused on gem crystals on matrix but eventually changed my taste and became more focused on quartz although I still collect other specimens as well.

So your specialty is quartz? Why quartz? How do you select specimens for your collection?

Quartz became my specialty gradually as I started to notice different quartz specimens at various mineral shows and in private collections. Quartz and calcite are among the most abundant mineral species in the world. And although they are very common, the truly aesthetic and unusual specimens of quartz and calcite are rare.

Since quartz is so common it has plenty of possibilities to produce specimens in a very diverse fashion and can occasionally become exceptional. The rarer mineral species become, the lesser the likelihood that the individual specimens will turn out large, aesthetic or otherwise exceptional in appearance.

In the past I also admired calcite greatly but as a chemist I appreciated quartz more because of its properties that make it more resistant and durable. However, I do have a nice calcite sub collection from Banská Štiavnica. As far as adding specimens to my collection the aesthetic aspect is number one priority to me.

As a collector and photographer, how do you value the quality of a specimen? Do you consider just aesthetics or also a provenance or scientific value? I bet you had in hands way more top specimens than most of us.

As a mineral collector and photographer, I appreciate mineral specimens mainly based on the aesthetics, but I appreciate other factors such as the locality aspect and scientific value too.

However, from the scientific point of view, I value mineral specimens primarily based on two parameters. One is “rare” or “exotic” chemical composition that are uncommon in minerals or do not occur in other parts or the world. The other aspect is unusual appearance such as a very specific structure that has not been found elsewhere.

For example, there are several type locality minerals in Slovakia some of which are interesting and produce collector’s quality specimens while others are mostly of scientific value only.

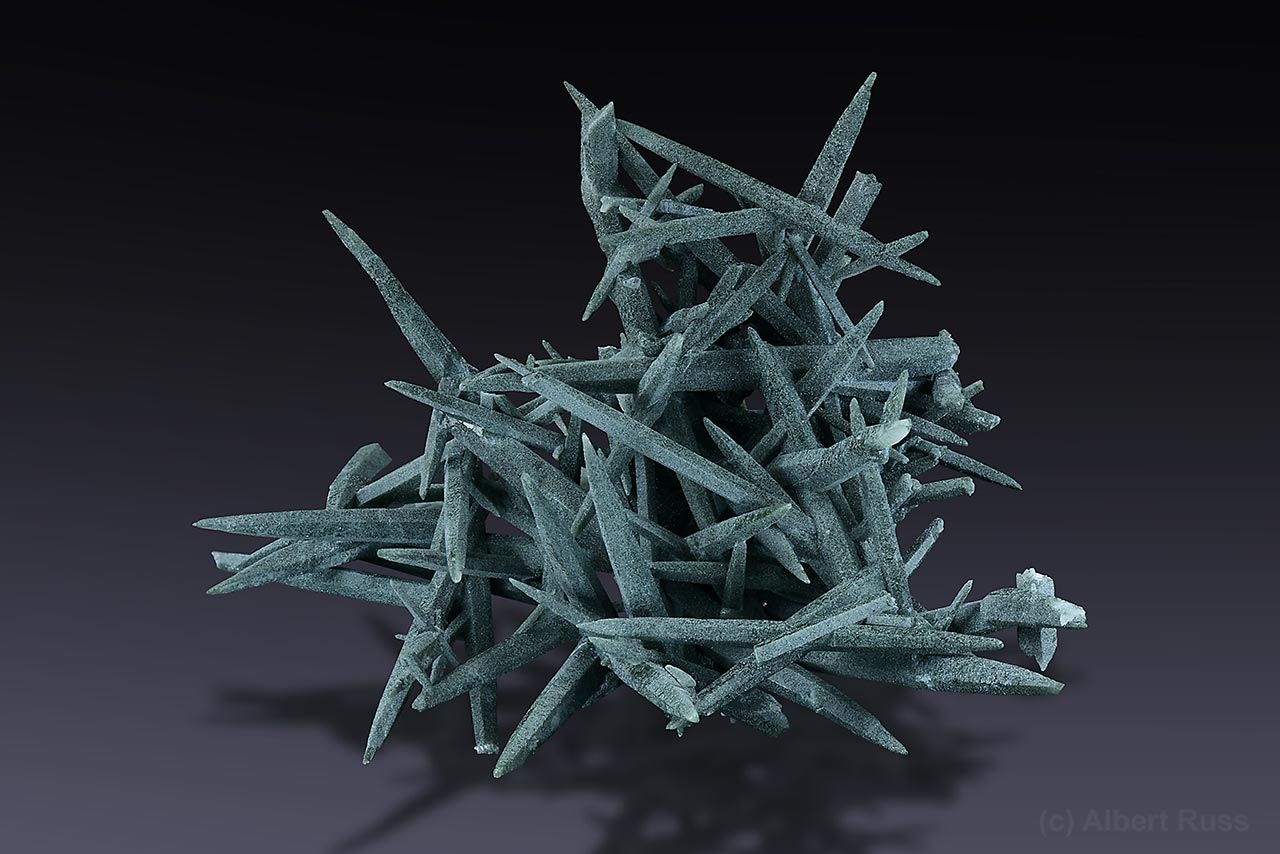

Devilline is a very rare secondary Cu mineral from Špania Dolina which has a very characteristic structure in well-developed aggregates. However, I have only seen several specimens which I find aesthetic enough to well exhibit its specific structure and all 3 of them are in museums.

Hodrušite, on the other hand, is just a rare mineral- it forms microscopic crystals and almost invisible aggregates and unlike devilline does not exhibit any specific combination of color and structure that would not be commonly found in other minerals. Thus, if I had the best known hodrušite in my collection, I would gladly trade it for a fine quartz.

How did you get into a mineral photography? I suspect you did not start directly with minerals.

No, originally I started to photograph ocean waves, surfing and various landscapes while living in the USA. I shot on film and although I tried a few mineral shots at the time, all attempts turned out so badly that I eventually gave up.

After the digital photography became more and more accessible, I retried shooting some of the minerals from my collection and the results turned out pretty good and kept me going. This was sometime after the year 2003. At the time I thought I did wonderful photos but now I think otherwise. I keep learning from my own mistakes and try to improve over time.

So what is more important to you – art photography or minerals? Do you have some dreams or goals in art photography?

This is actually a very difficult question. I always admired minerals and my interest in mineral photography has always been primarily to capture the beauty of mineral specimens. Looking at minerals of many private collections motivated me to photograph some of my favorite mineral specimens in those collections for my personal enjoyment and as a future reference of those specimens that I would never possess in my own collection.

This is how I realized I not only became a mineral collector and a mineral photographer, but had also merged the two - I became a very dedicated collector of mineral photographs. However besides mineral photography I also admire landscape, nature and abandoned mines and caves.

Sometimes it is difficult for me to decide what is more interesting or more important- whether to shoot the best mineral specimens or the most beautiful natural landscapes. If I had an unlimited budget, in all likelihood I would constantly travel around the world photographing the most fascinating landscapes as well as minerals. I would publish my travel encounters in art books just like I did my photography experience with ice a couple of years ago.

Before we dive into mineral photography, we might briefly mention your other obsessions. The first one is definitely ice. Why is ice so attractive for you?

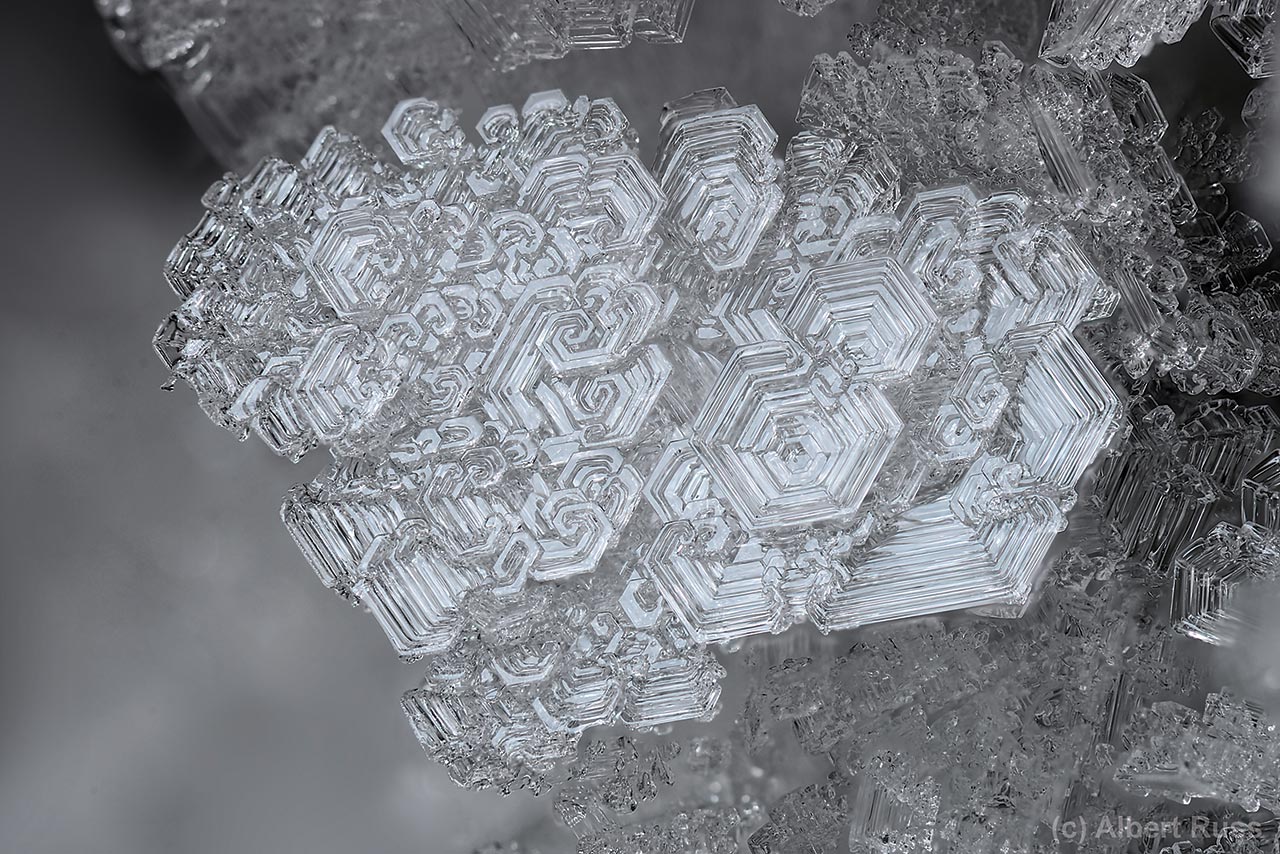

My passion in ice photography has emerged from two independent directions. Ever since I started entering abandoned mines in pursuit of adventure I noted weird, unusual ice stalagmites forming in Winter. In the early days, I tried to capture the simple beauty of these features but later noticed especially weird surface structures that have emerged on the ice surface after substantial thaw. Over the years, I tried to capture these thawing / etching structures that seemingly provided endless possibilities.

Eventually, I realized that I have built a rather vast collection of highly unusual images that resulted in my self-published book "Ice Metamorphosis". The core of this book exploits the diversity of images related to the thawing ice structures. My second direction in ice photography was definitely not something that I have discovered myself but rather saw as an inspiration in other photographer's work. This direction is related to ice caves and is in fact much more a passion with unfortunately very limited opportunities.

Ever since I saw the first amazing photographs of ice caves from Iceland, I craved to both experience and capture the beauty beneath the blue ice. One trip to Iceland and several trips to a small ice cave in Bavarian Alps was executed so far. Despite the fact that I had so few opportunities due to distance and access of these places, I think I did well in photography mostly due to my previous experience in abandoned mines.

Unfortunately, the blue ice caves of Iceland are becoming so popular and are attracting so many professional photographers that opportunities for further exploration in this otherwise very exciting field are diminishing.

Your other favourite subjects are abandond mines and photographing minerals in-situ. This is combination of quite dangerous and technically difficult photography. Could you briefly introduce this area of photography?

Many years ago, I was asked by a friend if I wanted to join him in a mine exploration with emphasis on photography in an abandoned mine in Pezinok, Slovakia. Although I thought it was a crazy idea, I agreed. Whatever I expected of the experience, it was still different and much more interesting. I realized that abandoned mines provide endless opportunities for photography and became addicted in this area of exploration.

At the same time I admit I was always somewhat afraid in the mines, not in the real panicky way but in a way consumed by the mystery and unknown of dark, enclosed, yet seemingly endless tunnels. Although I have visited several dozen mines over the years, I can only imagine that there is so much more to see.

Unfortunately, difficult access and sometimes intentional prevention of entering these mines due to whatever purpose is making mine photography more challenging every year. My passion of underground photography does not end in abandoned mines but it includes karst caves.

Unfortunately, caves are much less accessible for serious photography mainly because the issues of bureaucracy. As is quite common in Slovakia, success in accessibility is predominately related to the person's position, function and status in the society whereas knowledge, experience and talent are only of secondary importance. I am especially grateful to my friend Stanislav Jeleň for helping me access several caves in pursuit of fantastic photographic opportunities.

And now back to the minerals. Can you tell us about how you started and how to become a renowned mineral photographer?

My mineral photography was a long trial and error journey. I learned, improved over time, from time to time I was given a valuable advice from my friends. But I learned a lot just based on observation and evaluating my own mistakes.

My primary interest in mineral photography was to capture the beauty of minerals and keep the photos for future enjoyment. Eventually several friends noted me and supported me and praised me in public, so I was introduced to those who in turn were looking for photographing minerals just the way I was doing it. I made lots of additional friends in this process.

Publishing articles and providing photographs for various reports in Lapis, Rocks & Minerals and Mineralogical Almanac magazines also helped me get my attention. In the early stages it was Robert Brandstetter and Peter Lyckberg who had the most significant positive impact on my mineral photography future.

Robert introduced me to Lapis magazine and asked me if I could submit an article there. It turned out to be a great idea which set things in motion. As a mineral photographer himself, Robert also guided me in mineral photography and taught me a lot by being constructively critical.

Peter admired my photography beyond minerals. He introduced me more and more to the mineral world- collectors, dealers as well as other photographers. This way I met Bryan Swoboda, Ludmila Cheshko, Anton Watzl and many others.

There are many fields in mineral photography. What do you shoot most?

Now I mostly shoot complete mineral specimens but still find interest in close-ups and details, especially if it reveals some fascinating structure.

How do you select mineral specimens for photographing? Is that just a matter of business decision or do you shoot also something just for fun?

I used to only select those mineral specimens which I found appealing to me. If I shoot professionally, I have to photograph whatever is asked of me. Sometimes I “suffer” through photography of those “ugly” and rare minerals, but I am quite used to it. The worst combination is “ugly and complicated” when I spend excessive time making a satisfying image that hopefully will be approved.

However, there are few such occasions. Most often I really enjoy what I photograph. Even during professional photo session, I tend to pick out rocks that don’t need to be photographed but I shoot them anyway for the sole enjoyment.

How did you get into a professional mineral photography? Did customers reach to you, or did you actively seek some contract?

I got introduced to some customers by my mineral friends who recommended me as a photographer although they were already familiar with my photography. I remember one particular situation where I sought out Fabian Wildfang on Facebook based on his wonderful collection that was becoming more famous in the mineral community. I did not know Fabian personally at the time and was very surprised and thrilled when he invited me to photograph specimens from his collection.

In person we became good friends and shared our mineral passion from the artistic perspective. If I was asked to make a photo exhibit of my mineral photos, I would select more than half of images from Fabian’s collection.

Another fun experience was with Tomáš Buzrla. I was traveling across Moravian Highlands with a friend and ventured to the Galerie PATRIOT Museum. I heard about the museum and Tomáš but we did not know each other in person. I immediately recognized many specimens from the museum that I wished to photograph and at the same time Tomáš requested me to do just that. We became friends and I made several trips to the museum.

Back to the technical part. The typical question is which camera is best for mineral photography. Which equipment do you use and why?

I started with a Nikon D300 which got stolen from my car, so I temporarily used a Nikon D5000 and later went for a Nikon D600. Last year I figured my Nikon D600 was becoming very old and overused so I got a Nikon D850. I was happy with the D600 but tried something new for the sake of higher resolution, better image output and the feature of automatic focus stacking. I use Nikkor 105 mm macro for all my mineral photography.

The common cliché is that it's not about the equipment and good photographer makes a good photo with any equipment. What is your opinion?

In my opinion you have to have both a dedicated photographer and use good equipment to produce a good result. I have seen some casual photographers with obviously no understanding for light or composition using the best of equipment available that were producing images that were either technically wrong or of something that was either too uninteresting or boring to capture in such quality.

On the other hand, if you capture a really good series of images with a bad camera- you may be excited for a while but eventually you start to regret the image output- in terms of noise, resolution and so on. Performance of various cameras is quite variable so the better photographer you are or the better opportunity you get the higher chance you capture what you want with a better camera.

When I compare my D600 and D850 I regret not having the D850 much earlier as there were some opportunities that would have resulted in much better images have I had that camera at the time.

We have already seen mobile photos published in Mineralogical Record. Most of pictures posted on social networks or on the internet are mobile photos and videos. What do you think about mobile mineral photography?

Can minerals take their selfies? I hope not :D In any case, in my opinion true quality mineral photography can’t be achieved with a cell phone. I hope this won’t change for some time.

Unlike many other mineral photographers, you do not use a “Scovil background”. How do you handle your backgrounds?

This is true, I don’t produce a “perfect” background. What I do is take a photo of a mineral the best way I can and cut it out as a separate layer in Photoshop. Then I generate a background myself. I have come up with several ways how I do it.

This brings us to the other controversial topic, which is background swapping. Many photographers consider this as a fake or not a real photo. Why do you think this opinion is not true or why its obsolete?

I don’t consider creating an artificial background as fake or cheating. What’s important is the mineral specimen itself and if its surrounding area is not uniform, smooth or is in other way distracting, it’s better to create a new background that removes any distraction from the object of interest. There are advantages and disadvantages to this approach of course.

The advantage is the photo itself. You are not limited by what you can place around the mineral- you don’t have to worry if a mirror or a black cloth is placed next to a crystal for whatever reason that otherwise improves photography. Backlight, mirrors around and behind a specimen can greatly enhance the photography while ignoring the fact that they are actually there.

Some reflections or partial backlight can be achieved only in a certain way and focusing on background would prevent such possibilities. Thus, creating a perfect natural background can be a limiting factor for reflections and lighting in specific cases. For example, use of a mirror for a dark gemmy crystal enhances its color and transparency when placed directly behind a crystal which simply can’t be hidden in the background. In the original image the mirror is obviously there but disappears with post processing.

Also considering and planning of natural background can be a tedious and long work. Focusing solely on the object can produce a better result easier, and faster. In fact, shooting without considering background perfection is much faster.

The drawback to this is obvious- post processing takes a lot more time and work than the shooting itself. Sometimes I consume 80% or more of time during post processing- two days of shooting usually results in several weeks of photoshop work. However, keeping the multi layer files of images also helps if you have a desire to change the background, isolate the object or include it in another image.

Other very important part of mineral photography is light. Many photographers use big softbox, LED panels or diffused still lights. You strongly prefer daylight. Why and what is its advantage?

It’s perhaps unusual but that’s how I got used to it. Yes, almost always I rely on natural daylight. In natural daylight colors of many mineral specimens are true and on a cloudy day the gray skies produce uniform light that is perfect for even the most complicated crystals with very shiny surfaces.

One great advantage of natural daylight and working partly outdoors and partly indoors is the smooth transition in light directing. When outside the light is more or less perfectly diffused. However, if you are behind a window or by a door, the further inside you go, the more focused light becomes. This results in stronger reflection in individual crystal faces and greater contrast. It’s still not a beam of direct light but it’s not perfectly even either. By changing your distance from the door or window you can achieve the perfect reflections that you desire- with continuous precision.

Another advantage is incredibly simple setup. I can travel and shoot minerals anywhere I wish without the need to carry heavy and complicated equipment for my setup. Usually, I am fine with a chair, bench, or a table which is readily available almost everywhere. What I usually need to take with me is my camera, tripod, a few mirrors and a piece of white and black cloth.

If shooting at a mineral show, again I can arrive “light” and find the right area for my simple setup somewhere outside. The best and easiest setup for me at the Munich show are the large rock benches between the halls outside. The main problem with the natural daylight is changing weather, especially rapidly moving clouds. Since my mineral photography is so dependent on daylight conditions at least I know when to stop-I usually quit my work before sunset and can plan accordingly.

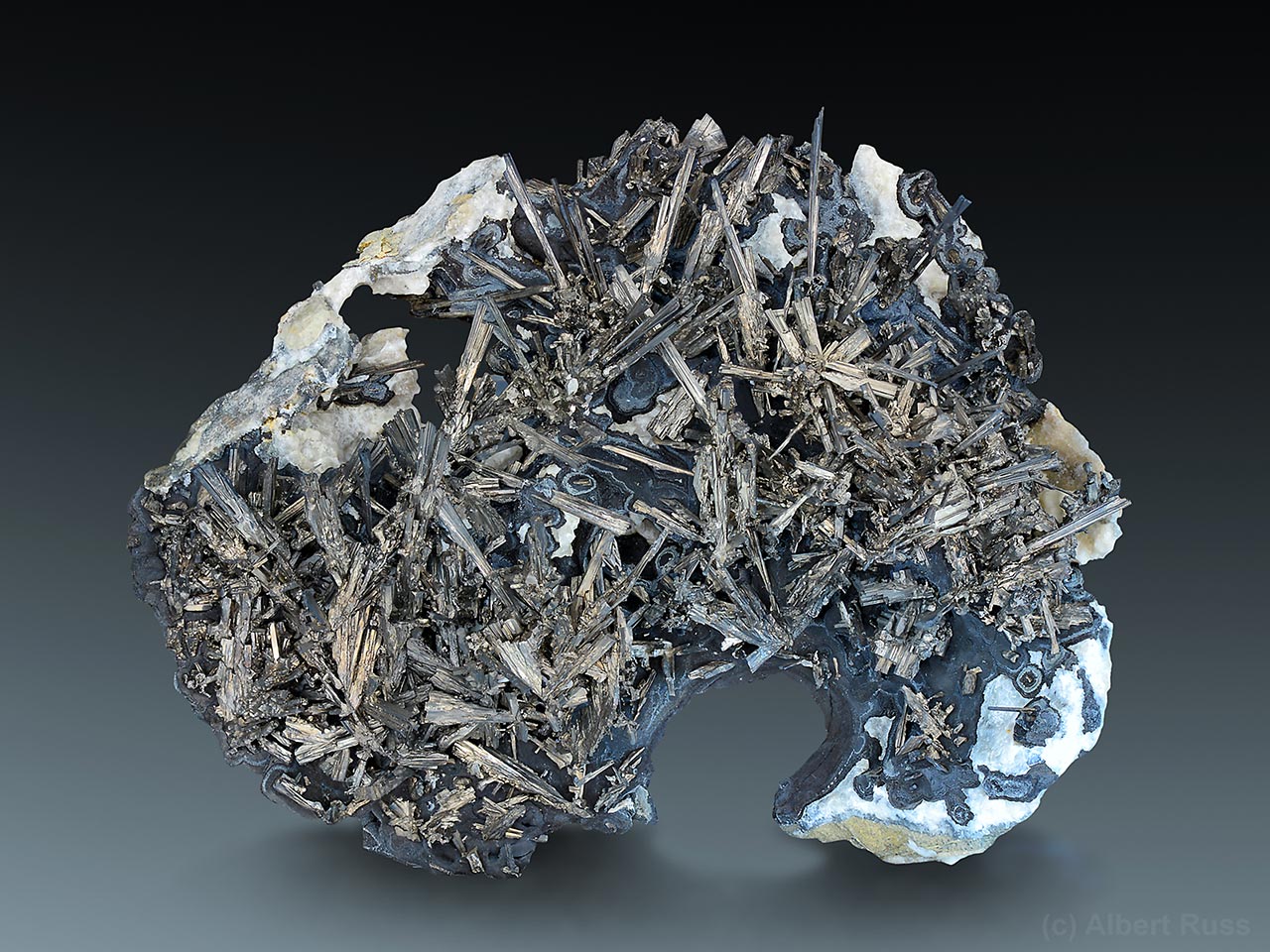

I also use a softbox which helps a lot with some specimens like clusters of stibnite crystals which reflect everything off of them. Such shiny specimens require a softbox because it becomes incredibly difficult to remove all unwanted reflections and produce sufficiently smooth reflections even in perfect outdoor conditions. Sometimes I try to photograph with the help of artificial light, but I do this only occasionally.

Another controversial topic is backlight. Obviously, it gives specimens unnatural look. Especially if you boost contrast and/or use contrast background too. What you think about this? Can you use some kind of backlight with daylight?

Sometimes I try to make a backlight but usually only to dark transparent crystals to enhance their color and transparency. Mostly I try to do this with a mirror in the back using the same natural daylight but simply placing more of it behind the crystals than around the specimen. Rarely I use artificial light source to make such crystals “glow”. Either way I try to combine the light so that the mineral specimens look as natural and beautiful as possible.

Most people consider couple dozen bucks per picture a fortune. "It’s just a click" is a common myth. Can you explain us a bit what it takes to create publication quality photo? How many shots you make? How much time is average shooting and processing per picture?

To make an acceptable mineral photograph- the one that makes you happy and meets needs of a customer, it takes a bit more than a click. Just the shooting process can be tricky - you have to adjust the light conditions using whatever equipment you have, select the right angle, do some trial photos and find the right position for the mineral and reflections.

If it’s satisfactory, you need to shoot a series of images to be stacked later. After you complete the series, you realize there was some dust present while checking some frames, you try to remove the dust and start again. Then you realize that the first position was better because when you cleaned the specimen you shifted the angle slightly but enough to influence the result. Then you try another angle and realize that the specimen is more green than blue or too yellow, so you change the setting.

In some cases of the most complicated specimens you are forced to improve whatever you’re getting. With the most aesthetic or the most important specimens you simply want to make it better because it’s an opportunity to make a really fine photo. So you shoot and shoot and reshoot. And reshoot the same series one more time just in case.

Sometimes you shoot so many series of photos that you need only a fraction to stack and process further so you think that you wasted so many frames, used up so much time for seemingly no reason. But it’s a natural part of the process.

Then comes the post-processing part, which can be anywhere between 20 minutes and 2 hours depending various factors. If the setup is right, usually I am able to photograph between 3-5 specimens per hour, in special cases 1 specimen per hour or even struggle with one for 2 hours. It would be a fair estimate that on average it takes me at least 1 hour to complete a photo, although it’s variable.

Also you don’t have a stream of mineral specimens coming on your table every day - you have to travel to photograph the collections, plan the trips and so on. In the end to make 100 fine mineral photos it’s not an easy or quick task to get rich. Also if you are required to shoot 50-100 frames per finished photo, working with different series for stacking, the camera is becoming overused quite fast.

Can you imagine being a full time mineral photographer? What does it take? What are the costs?

Of course, it would be a dream to be a full time mineral photographer. As of now it is not yet possible, but I hope to achieve this in the future.

There are way more highly skilled people than a decade ago in mineral photography. Are amateur mineral photographers a competition to you?

This is supposedly a pretty difficult question. Of course, the more photographers the bigger competition there should be. I have noted several very skilled and talented photographers emerge over the last decade.

As soon as there is support and demand for their art work, they can’t be considered amateurs anymore. It’s fun to see their work being presented on social media. In fact, this work influenced me and my vision in photography.

I have made friends with many of the new photographers, and I am happy to say that I have not seen any unhealthy competitiveness or hostility among us.

As of early 2020, the world has changed due to the pandemic. Did this influence your photography? How?

Of course, I think the pandemic influenced all of us in one way or another. During various restrictions and bad periods there were much fewer opportunities to visit friends and photograph private collections, especially abroad.

On the other hand, there was more time to experiment and reshoot some mineral specimens from my own collection as well as from collections of some friends living close by.

During this period, I obtained a new camera with added features, a new computer and learned several specifics which did significantly improve my knowledge in mineral photography as well as in software use and post processing. Some of this knowledge resulted in easier and faster photography while other approaches made the photography more difficult- but with a greatly enhanced output.

Do you see a future in mineral photography? Is it growing or not?

I think it’s growing, at least during this time period. With the advancement of new technologies in photography equipment and software, the quality of mineral images can be improved like never before. Also social media networks are playing a big role in presenting and promoting (as well as stealing) mineral photography.

There are several young talented mineral photographers that I’ve seen emerge over the last couple of years. It is hard for any of us to predict the future in mineral photography though. All I can say for certain is that mineral photography will always be directly related to mineral collecting.

If mineral collecting will expand in future, so will the interest of mineral photography and its demand. The beauty and nature’s art of fine mineral specimens will always require its capture in fine images for whatever purpose this might be. Minerals from some significant private collections can be admired online now.

Do you have some dreams, goals and plans regarding mineral photos? Where do you see yourself in the next decade?

Lately, I have enjoyed the process of being part of a book project, and have even self-publish a book or two. My dream is to self-publish a book from time to time that would be enjoyed by more people and would support the concept of mineral collecting. I have a long term dream to produce an art publication on Slovak minerals.

Recently I have cooperated on book projects with a very skilled mineral photographer Luboš Hrdlovič, who specializes in microscopic images. I admire mineral photography in a microscope so much that from time to time I think about going in this direction as well although I am well aware of the time and experience needed to achieve the desired results- and I simply don’t have time for that either.

Over the last couple of months, I have pushed my camera to capture smaller structures with the use of extension rings. It became possible to partly fill the gap between photography of regular mineral specimens and microscopic mineral photography.

This is a fun area that may have a potential for exploration for years to come. Otherwise, I am open to whatever comes my way- let us see what happens in the next decade.

Comments