Gold - The Yellow Metal

Gold is a bright yellow native element, long prized as an object of natural beauty. It has attracted the attention of human cultures for thousands of years, and its softness, resistance to corrosion and workability have made it a favored material for creating decorative jewelry and early coinage. Modern technological applications have displaced much of its historic use in jewelry and measuring wealth.

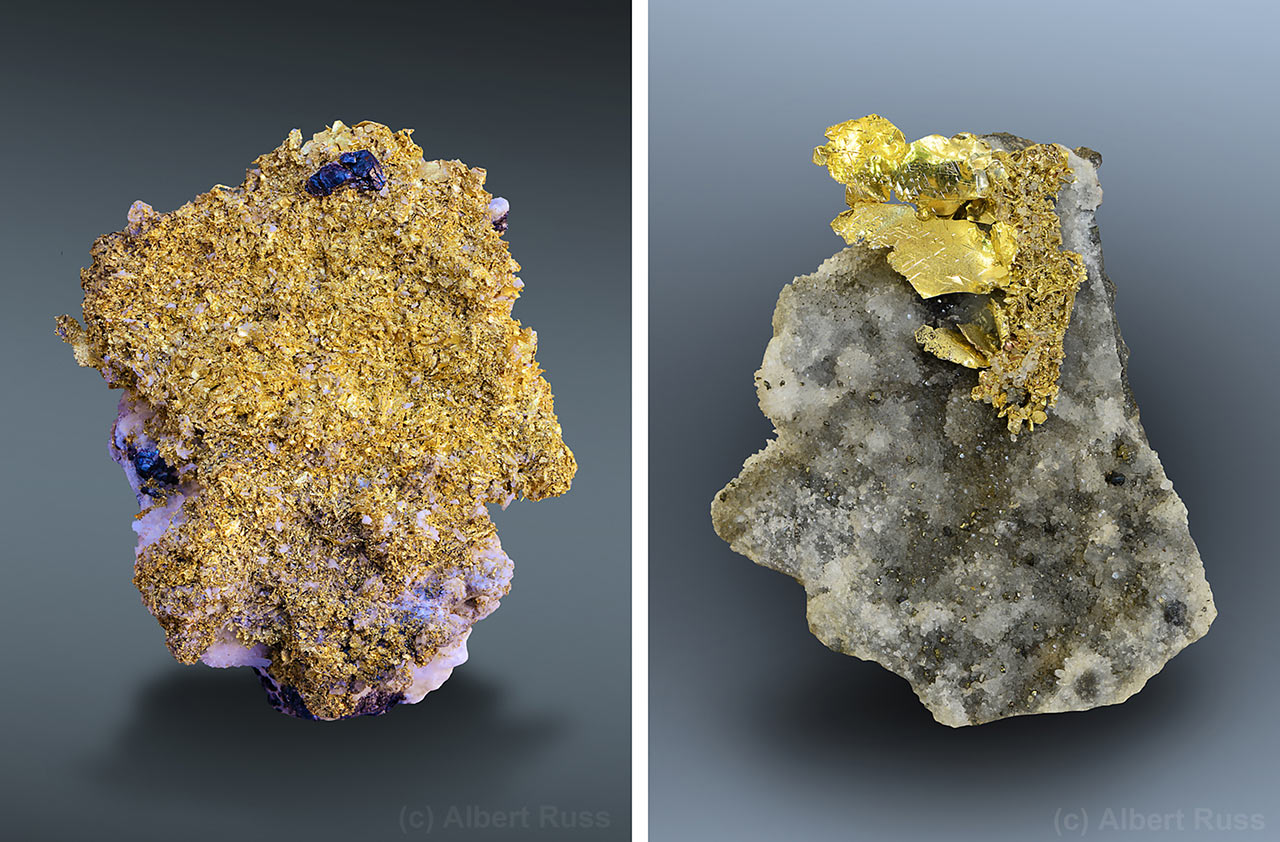

Crystal Structure of Gold

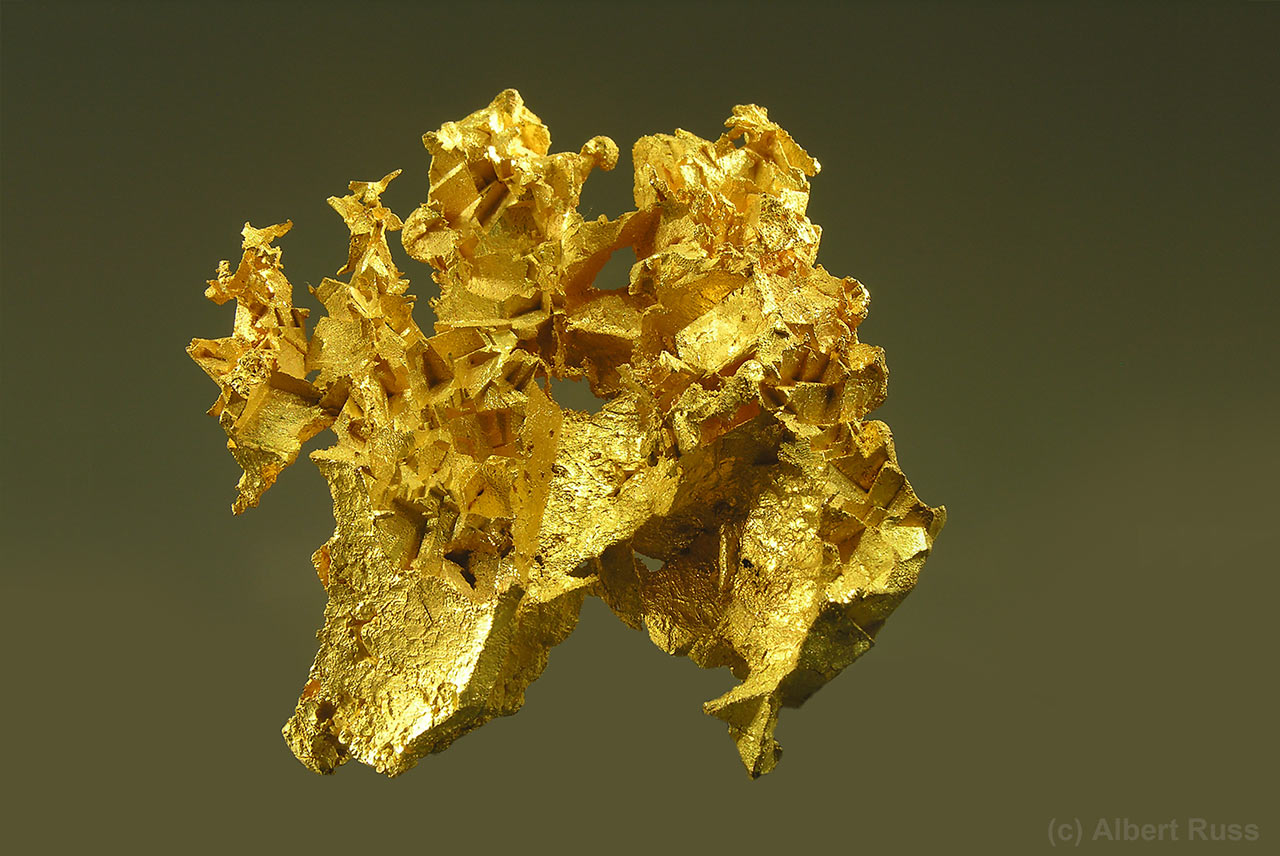

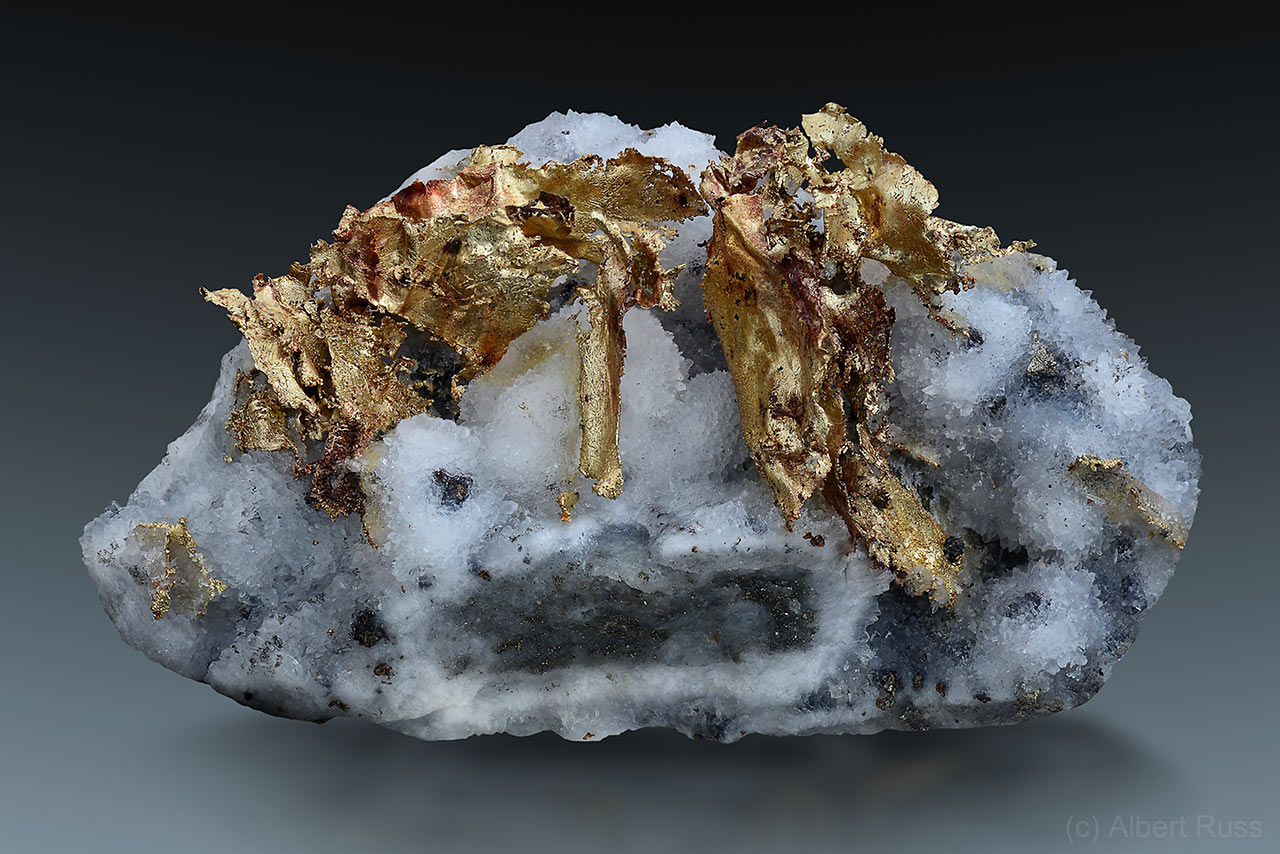

Gold occurs in the isometric crystal system, and its ideal manifestations are as cubic, octahedral and dodecahedral crystals, often occurring as crude to rounded versions of those shapes. In fact, gold also occurs in a myriad of other delicate habits, variously described as dendrites, arborescent, wires, nuggets, herringbones, encrustations, hoppers or spongy. Flattened grains or scales are labeled gold dust.

Gold frequently includes certain amount of silver, the gold-silver alloy is called electrum. Increased silver content imparts a whiter color.

Physical Properties of Gold

Gold is naturally lustrous, with a bright yellow shine. Its hardness is 2.5 to 3.0, easily scratched with a fingernail. Its streak is yellow. Gold is unusually dense, with a specific gravity of 16.0 to 19.3, depending on what it is alloyed with. Gold is sometimes confused with other common yellow minerals, particularly chalcopyrite and pyrite, but is easily distinguished from them by density, hardness and streak.

Gold is not usually thought of as a geochemically mobile element, but in fact is often observed or inferred to have traveled in hot solutions combined with the sulfide or sulfate complexes associated with mineralizing systems. As an element, it is unaffected by most solvents, and can only be dissolved in aqua regia (1 volume of HNO3 combined with 3 volumes of HCl).

The uniqueness of the metal is assured by four of its most important properties: resistance to corrosion, malleability, conductivity and tolerance of high operating temperatures. Its freedom from tarnish and discoloration, along with its workability, assured its longstanding popularity for jewelry. In the 20th century, its conductivity and heat tolerance opened up new opportunities for industrial applications.

Origin

Gold is perhaps most familiar to the general public as an element that accumulates as nuggets or flakes in stream beds, or perhaps as wires and flakes in the quartz veins. The true story of gold's origins is far more complex than that, however.

The most obvious discoveries of gold occurred when mountainous areas were eroded, and gold exposed at the surface gradually washed downhill and migrated into active drainages. For the gold to accumulate in any quantity, however, it was critically important for the drainage to encounter a shallower slope, so that the energy of the stream was lost and the gold particles dropped out of the formerly energetic stream flow. These accumulations are called placers, and have been the object of intense prospecting by individuals since time immemorial. There are simple techniques for examining stream sediments for gold: put some stream sediment in a shallow pan with water, gently agitate the pan and pour off the lighter fraction of sedimentary particles. Gold, being denser, will tend to settle to the bottom of the pan.

What are the ultimate sources of this gold, eroding from mountainous areas? Since the Middle Ages, theories and observation have focused mainly on visible veins carrying mixtures of quartz and free gold. Many such instances are associated with hot spring systems which represent the dying stages of long-lived volcanic activity near the Earth's surface.

These occurrences are in fact real and important, but they have been reduced to insignificance worldwide by the discovery of many more, larger reservoirs of gold. Two of the more important types are deposits called porphyry coppers and Carlin-type gold. Both types of ores were discovered when mining engineers realized that very small concentrations of gold could be mined profitably if the volume of mineralized rock was accessible and large enough.

Porphyry coppers are the result of a well-defined sequence of events. A large body of rock melts in the heat of the Earth's crust about 10 miles deep, and rises through the crust because its density as a semi-liquid magma is less than that of the surrounding rock. This rising bubble of melted rock contains water, copper and gold in solution. As the magmatic bubble rises into a lower pressure environment, it starts to boil off its contained fluids, and the loss of fluids forces the magma to begin to freeze in place when the crystals begin to congeal and interlock. The frozen magma continues to boil its included fluids while it is locked in place, and the usual result is an enormous explosion which causes the enclosing rock to fracture and allows the copper-gold solution to penetrate deeply, creating an ore shell. Generally in these systems, chalcopyrite (copper-iron sulfide) is the primary ore mineral, and gold is produced as a byproduct.

Carlin-type gold deposits are created from similar scenarios, with the important difference that the rising magma usually has a less explosive outcome, and it is invading a highly reactive environment of calcareous rocks, which tend to dissolve in the face of the advancing heat front, and allow the gold to precipitate from the migrating solutions. The result in a Carlin system is a widespread penetration of mineralization throughout a somewhat permeable zone of carbonate sediments. (Carlin is a tiny town in eastern Nevada, USA where this type of mineralization was first observed in 1960, and now much of eastern Nevada hosts millions of ounces of microscopic gold).

Placers today are the least important source of gold. Similarly, pure quartz-bearing vein systems are historically classic, but of reduced significance. Worldwide, Carlin-type systems - which are usually gold-only - are very important, but pale in comparison with porphyry coppers, which are found throughout the world in most tectonic boundary areas where oceanic and continental plates have been or are colliding, specifically the perimeter of the Pacific Ocean.

Current world production of gold is on the order of 3,000 metric tons (about 100,000,000 troy ounces). China, the largest producer, accounts for 15% of the total. The USA, Canada and Mexico, accounting for both porphyry coppers and Carlin-type deposits, account for another 15%. The countries bordering the Pacific Ocean, homes of porphyry coppers, account for about 20%. The remaining 50% is scattered among isolated African, Russian and other European countries.

Applications

Gold is one of the most unusual elements on Earth, in terms of its rarity, beauty, and its diverse unmatched physical properties. These attributes explain why it is valued and used in so many different settings. Gold usage can be broadly divided into two domains - the subjective area of value, and the objective area of physical usefulness.

In terms of subjective value, gold is honored for its fundamental beauty, and for centuries found direct application in jewelry. Historically, jewelry production dominated nearly all the demand for gold and was easily considered its most common use. More recently, gold has taken on an added role as a pure commodity investment, and its use in the investment markets, banking system and currency trading has displaced a large percentage of the former jewelry usage.

Gold is often the metal of industrial choice because its universal usefulness overcomes the disadvantage of its high cost. In the sphere of physical usefulness, gold is unparalleled in its value as a superb electrical conductor, a corrosion-resistant workhorse, an easily worked metal and a heat sink, able to tolerate high operating temperatures.

These four characteristics render it ideal for the following environments. Almost every one of the following listed electronics applications depends on at least two of these properties, the most important usually being conductivity and corrosion resistance: Telephones: switches, relays, contacts and wiring; Computers: edge connectors for socketed chips and plug-and-socket connectors; Miscellaneous small to large electronic devices: calculators, tablets, satellite dishes, GPS units, microwaves, TVs, laundry machines, stoves and refrigerators.

In medicine, new uses abound: Rheumatoid arthritis is treated with gold salts; Cancer is treated with microscopic radioactive gold particles in chemotherapy; CT and MRI scans employ nanoparticles in tumor detection; Gold reduces the risk of bacterial infection in ear implants, stents, and pacemakers.

In dentistry, gold has maintained its traditional value by allowing cavities to be filled with an inert, easily shaped and non-allergenic substance. Dentists have expanded the range of uses by alloying it with other elements to create bridges, crowns and other orthodontic appliances.

In construction, gold is finding new applications in specialized glassmaking for climate-controlled buildings, and in reflective coatings to reduce internal heating.

Occurrence of Gold

Most gold ore occurrences, even though found all over the world in rocks of every age, are not particularly spectacular or collectible. Depending on the geologic occurrence, gold may be visible and enchanting as a specimen or, more often than not, it may be mixed as submicroscopic particles with other ore minerals and be completely unremarkable. The result is that there are hundreds of thousands of small, isolated charming specimens from all over the world, collected by prospectors or mining staffs, but no localities that stand out as proven producers of museum-quality items.

Much of the reason is that most gold mining today is conducted on a strictly bulk-tonnage basis, where large volumes of rock are processed daily, and interesting specimens tend to be overlooked in such operations. Those rare, visually exciting finds are usually preserved for their specimen value, even if their weight would dictate valuing them for their higher intrinsic metal value.

Excellent native gold specimens originated on many localities worldwide. One of the most valued is crystallized gold from Eagle's Nest Mine in California, USA. Other mines in the U.S. include Red Ledge Mine, Harvard Mine and Mother Lode Belt in California, Round Mountain Mine in Nevada and many others. Many placer deposits with impressively huge nuggets are located in Alaska, South Dakota and California, USA and in Ontario, British Colombia and Yukon Territory in Canada.

South America has numerous world class gold deposits. Nice specimens were produced in Pauji and Icabaru in Venezuela and in Ouro Branco, Itaituba and Alta Floresta in Brazil. Lot of gold was produced in South Africa, impressive deposists are located also in Russia and China. Australia produced the biggest gold nugget ever, with Kalgoorlie, Western Australia and Bendigo, Victoria being the most famous gold-mining places.

Europe hosts some well known classic sites. Great specimens came from Cavnic and Rosia Montana in Romania. Other famous sites include Björkdal mine in Sweden, Brusson in Italy and Hope's Nose in England. One of the most aesthetic gold specimens were discovered in Křepice, Czech Republic in 1927. Great gold specimens were discovered also in Jílové u Prahy, Czech Republic and in Kremnica, Slovakia.

Comments