Staurolite – Mineral Properties, Photos and Occurrence

Staurolite belongs to the scientifically important but otherwise quite overlooked minerals. It is not very popular among mineral collectors, as most of the specimens looks similar to each other. Also industrial application of staurolite is very limited.

Crystal Structure of Staurolite

Staurolite is a monoclinic silicate with the formula Fe2+2Al9O6(SiO4)4(O,OH)2. It is further classified as a nesosilicate, a mineral composed of SiO4 tetrahedra connected solely by interstitial cations.

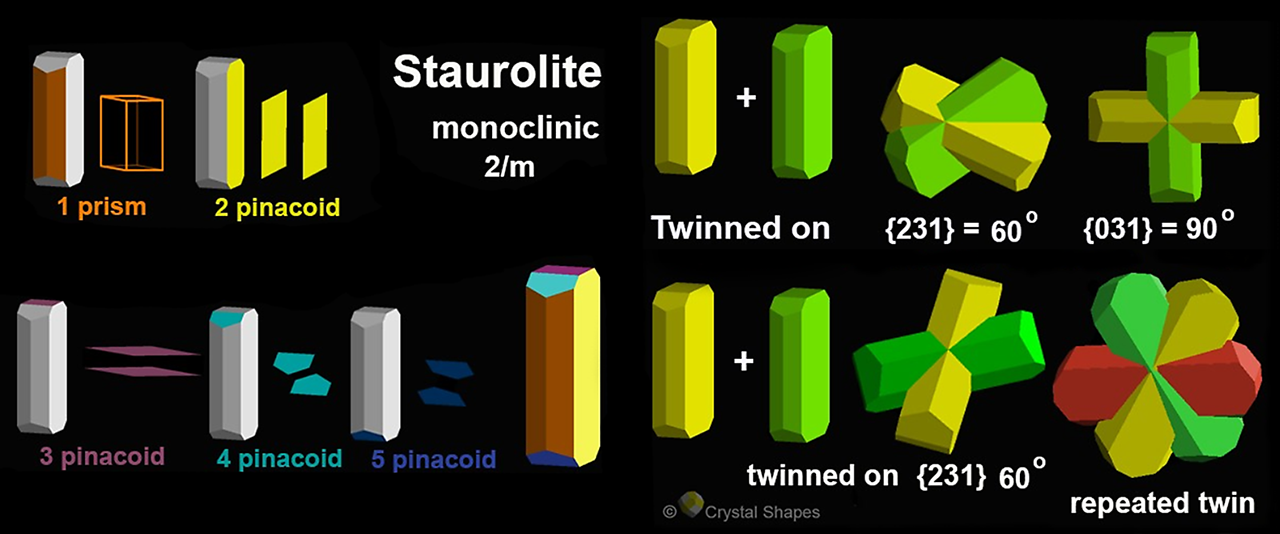

Crystals are usually prismatic and often twinned, but may be stubby or tabular. Visible crystals are prismatic and often form porphyroblasts (large crystals growing in a finer groundmass) in strongly metamorphosed terrains. In thin section, it often displays a “Swiss cheese” appearance in association with poikilitic quartz (large crystals of one mineral enclosing other smaller minerals).

Staurolite very often occurs twinned as 60° X-shaped twins, or as 90° cruciform penetration twins. Varieties of 90° crosses are described as Maltese, if the 4 ‘arms’ are of equal length or Roman, if the two sets of arms are of unequal length, as in a Christian crucifix.

Magnesium, zinc, cobalt, and manganese can substitute in the cation iron site, and trivalent iron or chromium can substitute aluminum.

Physical Properties of Staurolite

Staurolite ranges from reddish brown to blackish brown; rarely, it is blue. It is mildly pleochroic from colorless to pale to golden yellow in its X, Y and Z planes, respectively. It is transparent to opaque in thin pieces.

Staurolite is quite hard with Mohs hardness of 7.0-7.5, its streak is white to grayish, and its density is 3.74-3.83. Cleavage is distinct on {010}. Its luster is subvitreous to resinous to dull. Fracture is uneven to subconchoidal.

Varietal Names

Twinned (often polished or dyed) crystals may be sold at retail as Fairy Stone or Fairy Cross, a name originating in legend. Other cross-related names are croisette, angel cross, and faith cross.

Various accounts attempt to explain the legendary term Fairy Stone or Fairy Cross. The names are particularly attached to a site in Patrick County, Virginia, now a State Park. There, the bedrock and grounds are littered with small cruciform specimens of staurolite. The various legends connect a host of angels weeping stone tears at the moment of Christ’s crucifixion.

In one variation of the legend, the weeping is independent of geography, and just happens to be remarkable on the grounds of the State Park. In another, the weeping reflects the Cherokee Indian Nation’s ‘Trail of Tears’ as it was forcibly relocated in 1838-1839 from the southern Appalachians to Oklahoma. In still another variation, the weeping is directly tied to a race of ‘little people’ believed to inhabit springs in the area of present State Park, who wept upon learning of the crucifixion.

Solid Solutions and Polymorphs

Staurolite is the most common member of staurolite group. The other two group members are rare and both have just a few localities worldwide:

- Magnesiostaurolite Mg(Mg,Li)3(Al,Mg)18Si8O44(OH)4 – is a product of complex substitution and was first described from Gilba Valley, Piedmont, Italy.

- Zincostaurolite Zn2Al9Si4O23(OH) – was first described from Brunegg Pass, Valais (Wallis), Switzerland.

Lusakite is a cobaltoan variety of staurolite with part of iron replaced by cobalt and magnesium. It was first described from Lusaka, Zambia.

Naming and Discovery

Staurolite is habitually explained as named from the Greek stauros (“cross”) and lithos (“stone”), in reference to twinned behavior.

In view of the obvious cross-like appearance of cruciform twins, it is easy to assume that the conventional explanation (Greek derivation) is self-evident. However, Biblical scholars question whether the term stauros actually meant “cross” in classical Greek.

Homeric use of the word in the Iliad and the Odyssey always referred to stauros as an “upright stake,” and this was still the usage in classic Greek texts and the New Testament referring to the crucifixion of Christ. These scholars suspect that stauros acquired the meaning of “cross” in later centuries.

Origin of Staurolite

Staurolite is considered one of the index minerals that record the likely temperature and pressure conditions of terrains which experienced intermediate to high-grade metamorphism of aluminum-bearing parent sediments.

The normal suite of associated minerals would include almandine (iron-rich) garnet, muscovite, biotite, albite (Na-plagioclase), and sillimanite/kyanite, the ensemble indicating temperature and pressures at or above the ‘triple point’ (500° C, 3.7 kb), the estimated point in P-T space where the Al2SiO5 aluminosilicate polymorphs andalusite, sillimanite and kyanite coexist.

A seminal Ph.D. dissertation published in 1969 (Carmichael, D.M., 1969, On the mechanism of prograde metamorphic reactions in quartz-bearing pelitic rocks. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, v. 20, pp. 244-267) confirmed the significance of staurolite as the index mineral which, when coexisting with other minerals, marked the attainment of, and stable equilibrium at, the triple point in prograde metamorphism.

The generic reaction was suspected to be:

(1) staurolite + muscovite + quartz => aluminum silicate + garnet + biotite + water

Carmichael, supported by exquisite microscopic petrography, mass-balance calculations and thermodynamic data, was able to create stochiometrically balanced equations supporting the reaction:

(2) 9 staurolite + 1 muscovite + 5 quartz => 17 sillimanite + 2 garnet + 1 biotite + 9 H2O

This research was carried out in Ontario, but its validity has been confirmed in multiple instances in the metamorphosed fold belts of the northern Appalachians of New England.

Staurolite Applications

Staurolite is a favorite collector’s mineral, and the cruciform varieties are popular among Christians as amulets and brooches. One reason for staurolite’s popularity is that crystals often occur as large well-shaped crystals in a fine grained soft matrix: they are easily liberated as independent objects.

Collectors should be forewarned, however: The surface texture of natural specimens is normally pitted; smooth surfaces may be the result of polishing before retail sale. And specimens containing gas bubbles are more likely than not to have been manufactured.

The role of staurolite in industrial applications is restricted to its use as an abrasive when a material slightly harder than quartz is required. It is produced as a byproduct of mining titanium-bearing (ilmenite and rutile rich) sands and is recovered by hydraulic gravitational separation.

Occurrence

There are numerous sources worldwide of single and twinned floater crystals. Staurolite is common in staurolite schists and in some other types of metamorphic rocks. However, there are not that many localities with nice cross-shaped twins combined with soft and contrasting matrix. Staurolite never occurs as a free crystals growing into any vugs or fissures, it is always embedded in hostrock matrix.

Perhaps the most famous US locality is the Fairy Stones State Park in Virginia, referenced above, but other prolific US localities include Cumberland County, Maine; Grafton County, New Hampshire; Fannin County, Georgia; Blanchard Dam, Minnesota; Island Park, Idaho; and Taos, New Mexico.

In Europe, notable localities include Selbu, Norway; Brittany, France; Fanzeres, Portugal; Nový Malín, Czech Republic; Pizzo Forno, Switzerland; and probably the most famous staurolite locality worldwide - the Keivy Mountains in the Kola Peninsula, Russia.

Minas Gerais in Brazil; Mt. Isa in Queensland, Australia; and Antananolofotsy, in the Betafo District of Madagascar round out the list of established sites.

Comments