Native Platinum - Properties, Photos and Occurence

Platinum is a commercially valuable metallic native element, prized for its physical resistance to chemical and temperature assault, its ductility and malleability, and its utility in enabling catalytic reactions. It is also a precious metal and in the natural form also a rare collecting asset.

Crystal Structure of Platinum

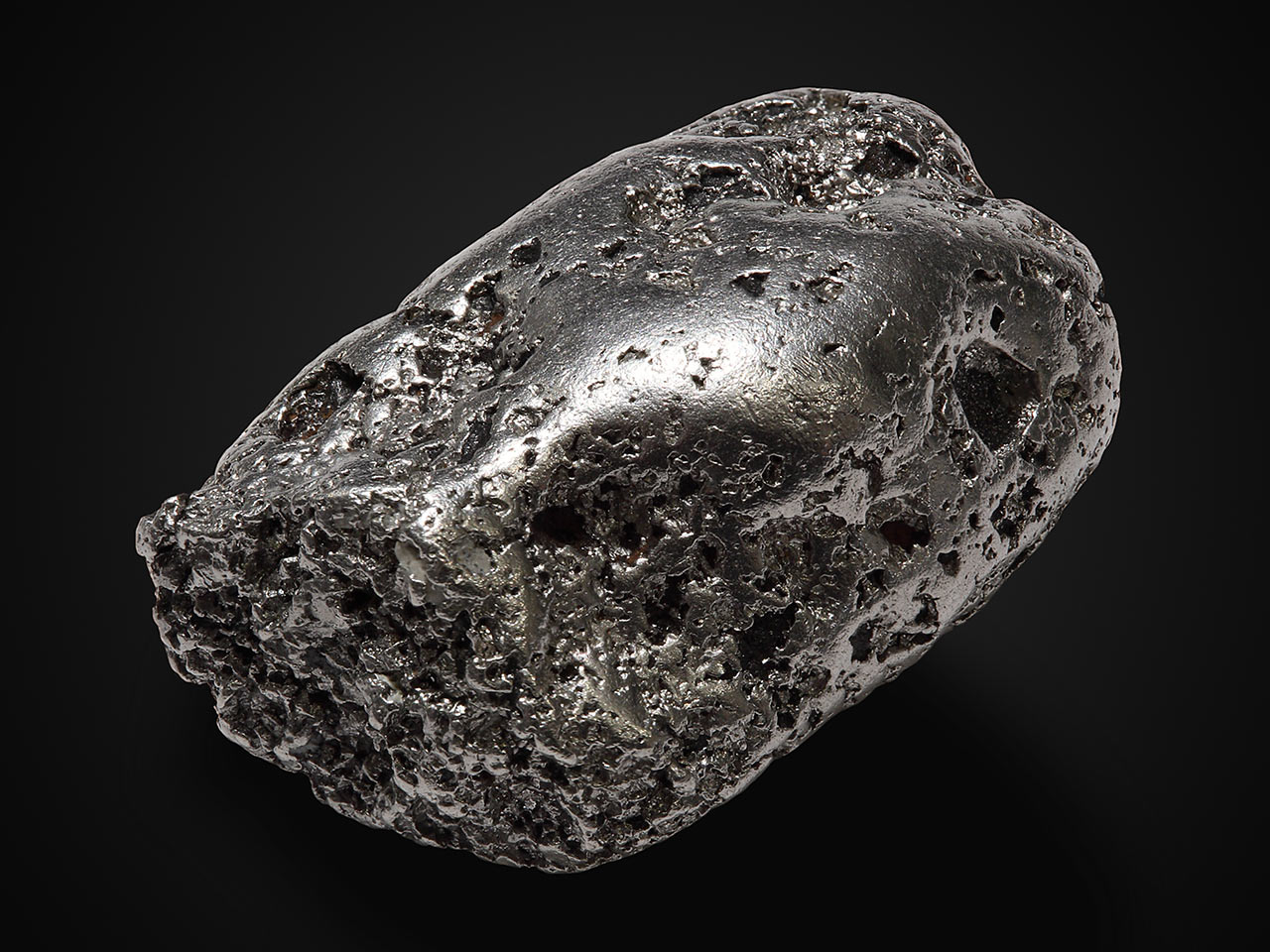

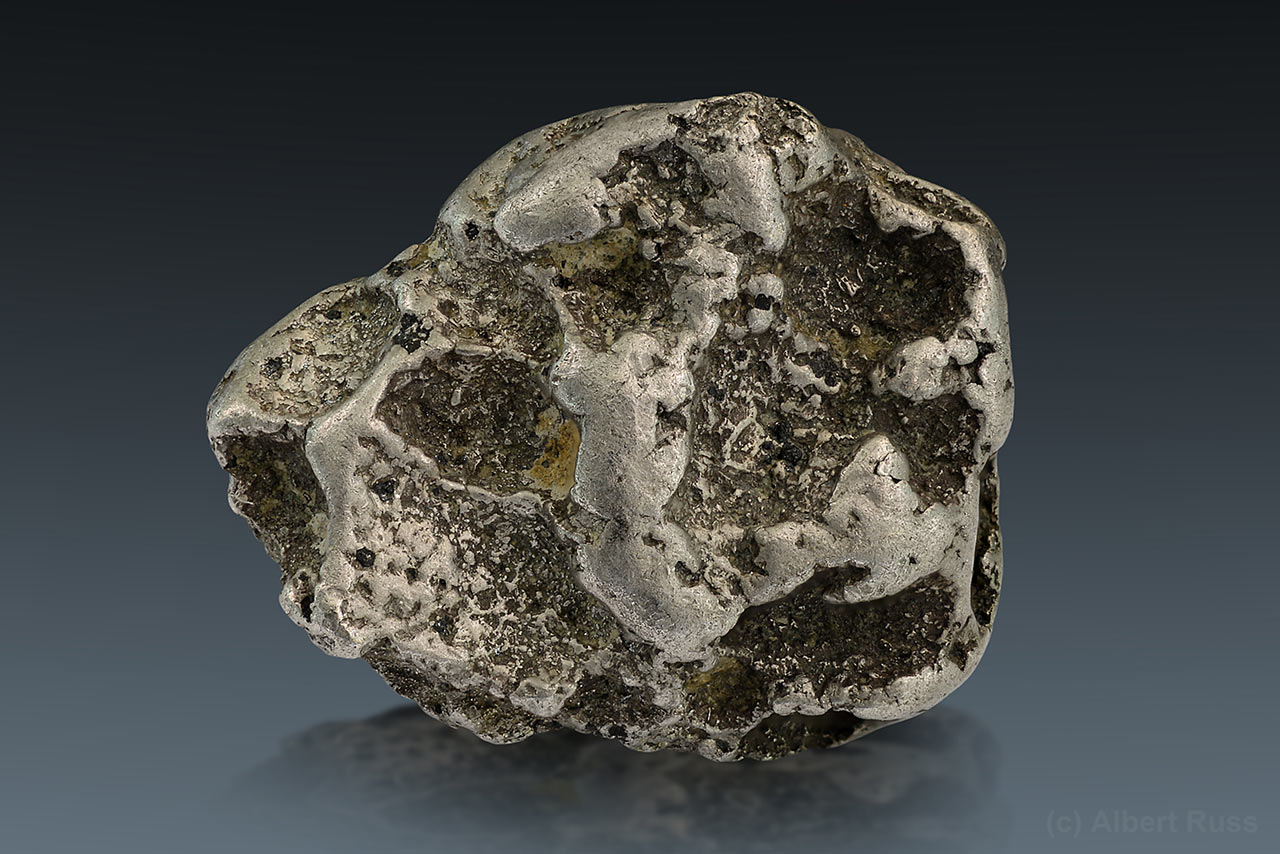

Platinum crystallizes in the isometric crystal system, described as face-centered cubic. Crystals may have rounded corners, and can feature penetration twins. Crystalline platinum can appear flaky or dendritic; alluvial specimens will appear as waterworn nuggets.

Unlike other precious metals, platinum does not belong to the copper (gold) group but to the platinum group elements (usually labeled just as PGE). Platinum readily makes alloys with both native palladium (Pd) and native iron (Fe). In fact, pure platinum is quite rare and crystalline specimens labeled as platinum are often crystals of isoferroplatinum (Pt3Fe).

Native platinum is isostructural with all copper group elements (Au, Ag, Cu) and of course with other platinum group elements (Pd, Ir, Os, Rh) - but not with iron. The small amounts of iridium (Ir), osmium (Os) and rhodium (Rh) are common impurities in the native platinum, less common are gold (Au), nickel (Ni) and copper (Cu) impurities.

Physical Properties of Platinum

Platinum is silvery-white, but also shades into tin-white, silver-grey, steel grey and dark grey. It is noteworthy for its ductility, malleability, high density, and lack of chemical and temperature reactivity. It is stable at high temperatures. Although described as corrosion-resistant, it will react with halides (fluorine, chlorine, bromine, iodine) and sulfur. Platinum is insoluble in HCl and HNO3, but it will dissolve in hot aqua regia. It also slowly dissolves in HCl in the presence of hydrogen peroxide.

Platinum luster is metallic; its hardness is 3.5-4.5. Platinum streak is silver-grey and shiny; and its density is extreme at 21.45, but decreases to less than 20 near its melting point of 1769ºC. Impurities in natural native platinum lower its density to 14-19, and iron impurities may impart a slight level of magnetism. Fluorescence is absent.

Pure platinum is so ductile it can be extruded as an extremely long and thin wire.

Naming and Discovery

Platinum owes its name to the Spanish term platina (“little silver”).

Historically, pre-Columbian natives near Esmeraldes, Ecuador had collected elemental platinum from alluvial sands, and made white gold-platinum artifacts from it circa 600 BC – 200 AD, on the basis of second-hand finds identified by archaeologists familiar with the antiquities trade. There are no direct archeological examples to rely on. The articles so identified appear to be an amalgam of a naturally occurring mixture of platinum-group metals.

The first documented reference appears in 1557 in a tract by an Italian, Julius Caesar Scaliger, who described an unknown metal thought to be an impurity in gold. During an 8-year trek through South America, Antonio de Ulloa (1716-1795) described Native Americans mining alluvial platinum in Colombia and Peru. De Ulloa was a man of diverse accomplishments, possessing an international scientific reputation owing to his participation in the French Geodesic Mission to Ecuador (to measure an arc of meridian at the Equator) and his writings on extensive travel in South America. Upon returning to Spain, he established the first mineralogy lab and wrote up his observations on the specimens in 1748. His report generated the first serious interest in the material, although he never followed up on his initial discovery. In succeeding years, other Europeans located and studied other occurrences in the New World, remarking on platinum’s high resistance to heating. Its malleability was not discovered until years later, when the presence of impurities was identified as the cause of the brittleness of specimens under study.

Origin

Platinum characteristically occurs in intrusive ultramafic rocks like pyroxenites, dunites, peridotites (rocks very high in Fe, Mg, and usually also Cr, originating deep in the Earth’s crust), and some gabbros. These rocks are the result of large volume intrusions of basic magma into the Earth’s crust. Very often, these intrusions display a long, complex cooling history where large pulses of magma were repeatedly injected into the bowl, settled with slow crystallization, and created pronounced layering of sulfide-rich mineral horizons dominated by platinum, nickel and copper. This process is generally known as magmatic segregation.

Platinum from ultrabasic intrusions is very often associated with diopside, olivine, chrome spinels, and various sulfides. It also occurs together with various tellurides, antimonides, and arsenides.

Much less common is platinum occurrence in certain types of quartz or quartz-hematite-chlorite hydrothermal veins or in some contact metamorphic deposits.

Applications

Platinum, although relatively rare in the Earth’s crust, is actually more abundant than the other metals in its group (rhodium, osmium, iridium and palladium), but it commands a significantly higher price because of the high demand for it in irreplaceable laboratory and industrial applications.

In the laboratory, platinum is the favored metal for bowls, crucibles, filters, wire mesh and electrodes, uses requiring resistance to corrosive acids and high temperatures.

Industrially, platinum is a fundamental catalyst in the upstream and downstream operations of the petroleum industry. Upstream, it is an essential component of the refining process, ‘cracking’ raw crude oil and facilitating its separation into multiple end-use petroleum fractions. Downstream, it is combined with another catalyst, palladium, before the muffler in automobile exhaust systems. The combination of platinum-palladium activates the low-temperature oxidation of unburned hydrocarbons to produce carbon dioxide plus water.

Platinum and palladium both compete for primacy in the world of catalytic converters. The competition is influenced by three independent factors:

- Historically, both platinum and palladium have each been effective catalysts in gasoline engines, while palladium has proven impractical in diesel engines. Recent technology improvements have allowed converters in diesel engines to accept loadings of up to 50% palladium. Lower sulfur content of diesel fuels also permits more use of palladium.

- There is a constant back-and-forth in Western countries over the relative acceptability of gasoline vs. diesel usage in passenger cars and light trucks, both in Europe and the U.S. Typically, gasoline emissions are responsible for chemical pollution, while diesel engines generate particulates. Municipalities and countries on both continents continue to rely on inconsistent pollution-control policies subject to serial revision.

- The long-term implications of the growth in the electric vehicle industry will also impact the outcome of the choice between gasoline and diesel motive power. Under any reasonable scenario, diesel fuel will dominate the trucking industry for the foreseeable future, by virtue of its higher energy content; the future of gasoline engines is much less secure.

Platinum is used in modest amounts as jewelry; although it does have a high bullion value, such that the owner fully appreciates its dollar value, platinum’s shiny silver-white appearance does not set it much apart from other, less expensive substitutable metals, such as silver, palladium or chromium. Gold, less expensive than platinum, has more cachet for its ‘bling’ factor. On the other hand, high-end watchmakers use platinum in the production of limited-edition watches, since the surface does not tarnish or wear out with use.

Platinum has one other claim to fame. For 90 years, a cylinder of pure platinum held sway as the official exemplar of the mass of one kilogram. The cylinder, designated as the “Kilogram of the Archives,” created in 1799, resided in France until 1889, when it was replaced by a similar cylinder of a 90/10 platinum/iridium alloy. This version was designated as the International Prototype Kilogram (“IPK”).

To assure continuing integrity, a large number of copies were made and distributed to interested countries for ongoing reference. The intent was to make the standard available for general use without the need for constant validation of its stability. Nevertheless, certain copies were reserved for verification: 6 sister copies resided in the same French vault as the original IPK; 10 working copies were reserved for ‘routine use’ and 2 for ‘special use.’ Numerous ‘national’ prototypes were dispatched worldwide. Only 3 official verifications were conducted, in 1889, 1948 and 1989.

Ongoing evaluations of all the cylinders against each other made it very clear that the entire worldwide ensemble of prototypes have been slowly diverging from each other, each cylinder losing or gaining up to 50 micrograms, to the point that it has become impossible to determine which of the many exemplars retains the true value. In November. 2018 scientists attending the General Conference on Weights and Measures in Versailles voted to redefine the kilogram in terms of a fixed value of the Planck constant, 6.62607015 × 10-34 kg.m2.s-1. The IPK remained in force as the world standard until May 20, 2019.

Occurrence of Platinum

The prime economically-valuable examples of the ultramafic magmatic geologic environment are the Bushveldt Complex in South Africa, Norilsk in Russia, and the Sudbury Irruptive in Canada.

The Bushveldt Complex is platinum-rich in one horizon, the Merensky Reef, containing about 75% of the world supply. Norilsk and Sudbury are both noted for large co-product platinum production by virtue of their enormous production of nickel and copper. There are numerous other examples of ultramafic complexes in the world, some mineralized and some not, but they are all generally characterized by their large footprint, great age, sourcing in the mantle, and prominence in exposures of continental crust.

Alluvial platinum deposits are recognized throughout the world, although their economic significance pales in comparison with the igneous deposits.

In Colombia, on the Pinto River, near Papayan, in the Department of Choco – platinum type locality.

In Australia: Platinum nuggets from Fifield District, New South Wales.

In the USA: The only commercial mines of platinum are located in the Stillwater Complex (Stillwater, Sweetwater, and Park Counties), Montana. In Alaska, from Platinum Creek, Goodnews Bay. In California, in a number of placers, as in Trinity County; and at Oroville, Butte County. In Oregon, at Cape Blanco, Port Orford, Curry County.

In Canada: In Ontario, at Lac des Iles Mine, near Thunder Bay – the only commercial platinum-palladium mine in Canada. In Quebec, at Riviere-du-Loup and Riviere des Plantes, Beauce County. In British Columbia, on the Fraser and Tranquille Rivers in the Kamloops District. In Alberta near Edmonton, on Granite, Cedar, and Olivine Creeks, and on tributaries to the Tulameen River in the Similkameen District.

However, the best platinum mineral specimens – from collector’s perspective – come from Russia. The great platinum nuggets and specimens originate at Konder (Kondyor) Massif, Khabarovsk Krai (Far East) and Is River, Nizhnyaya Tura, Sverdlovsk Oblast. Infamous place is Norilsk in Siberia, which hosts huge nickel and coal mines with significant production of platinum as byproducts. Norilsk district belongs to the most polluted places on Earth. Some specimens can be labeled as Talnakh, which is now part of Norilsk city. Less known is the platinum placer at Ledayanoy Ruchey, Koriak, in the Kamchatka Peninsula.

Comments