History of Klondike and Nome Gold Rush Events

The Klondike (Yukon) Gold Rush holds the record as one of the shortest-lived mining booms ever, lasting a scant 2 years, from August 1896 to September, 1898, when it was undermined by the slightly longer-lived Nome (Alaska) Gold Rush (September 1898 to 1905).

The Early 19th Century

Before 1850, there was little interest in the mineral potential of northwest Canada. Indigenous Native tribes traded some in copper, but placed no value on the gold they knew about. Furs were a far more valuable commodity, interesting both the Russians venturing from Siberia and Canadians venturing from Hudson's Bay.

A smattering of prospectors, including Ed Schieffelin, the discoverer of silver at Tombstone, in Arizona Territory, reconnoitered the area of the Fortymile River in the 1880s and discovered enough gold to develop a small town known as Fortymile City. The only consequence of this prospecting activity was the opening of new trails through the area. At the same time insignificant amounts of gold were observed along the Yukon, leading to the establishment of small camps where miners traded with the Natives.

The Klondike Discovery

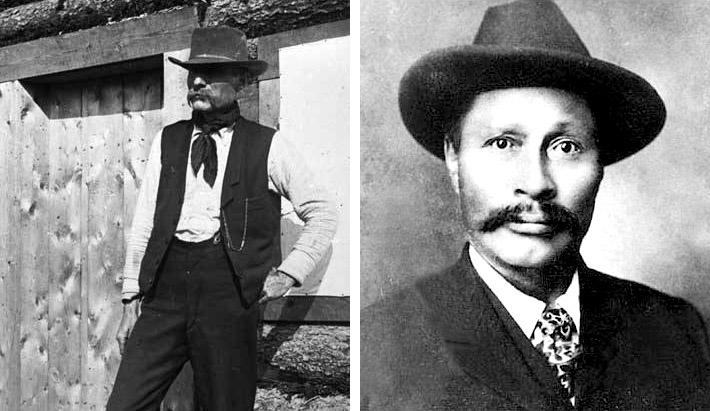

Four local miners - George Carmack and his wife Kate, Skookum Jim Mason and Dawson Charlie - discovered significant quantities of gold further upstream on the Yukon in August, 1896. Property ownership was not legally available to Natives, who were not considered citizens, so only non-Natives could acquire title to mining claims. The exploration party included a Native, who was deliberately omitted (by mutual consent) from the filing of the mining claim for fear that the claim could be invalidated.

Within a month, the original set of 4 claims on one tributary had been overwhelmed by a local land rush, and the early miners and speculators began a dizzying round of purchasing and selling newly claimed ground, and hiring others to work for them.

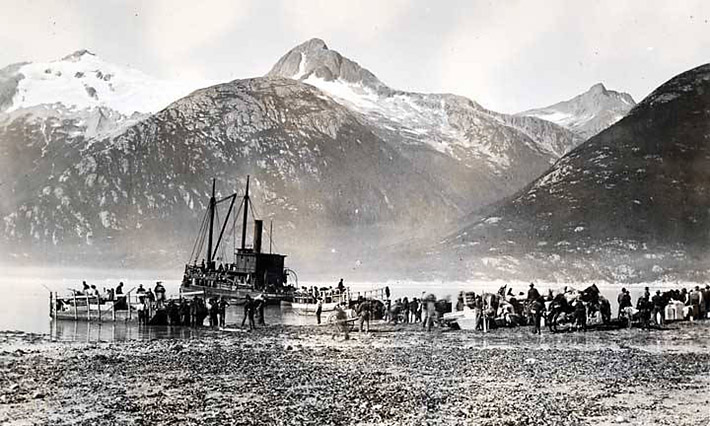

News of the discovery did not reach Seattle and San Francisco until June, 1897, when the first boats were able to leave the ice-bound area and reveal the scope of the find. The rush officially began on July 15, 1897 from San Francisco and two days later from Seattle as a result of the arrival of two ships carrying an estimated $1 billion worth of gold at current prices (~$1,000 USD/ounce). An estimated 100,000 prospectors stampeded for the Yukon.

Two factors seemed to be driving the mass of humanity northward. There had been several bank failures and recessions in the 1890s tied to the relative shortage of gold in relation to the paper money supporting it, and this led to gold hoarding. The abundance of gold reported from the Klondike seemed likely to satisfy a huge shortfall of gold in the developed world.

The second reason was purely psychological: As one historian described it, the Klondike was just far enough away to be romantic and just close enough to be accessible. It was also a superb opportunity for the Pacific coast to undertake a new period of growth.

Klondike: Embarkation for the Promised Land

The mania for migration infected people with absolutely no experience in the mining industry. Stories are legion of mass resignations of salespeople, clerks, municipal officials, police, firemen and the like. Most were said to be recent immigrants to the US.

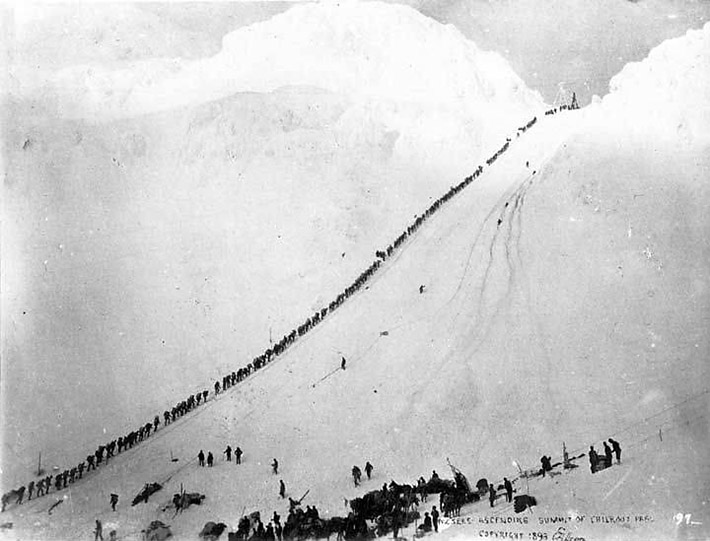

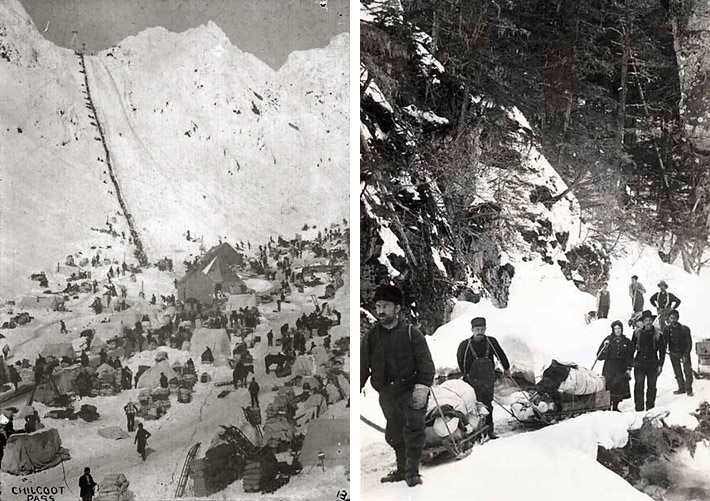

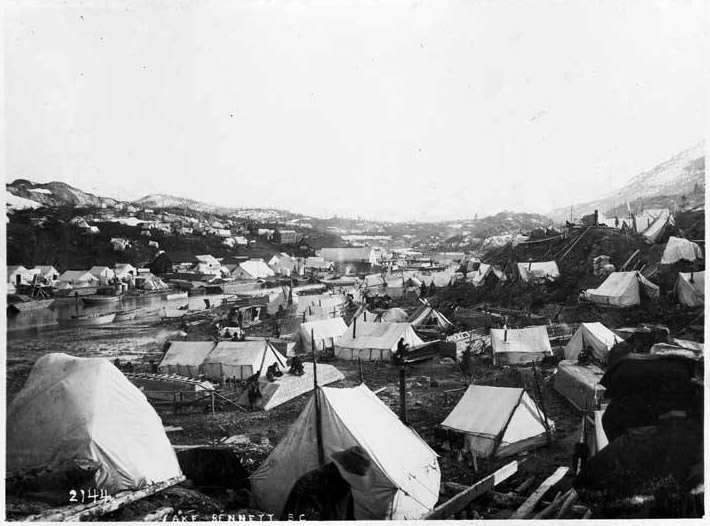

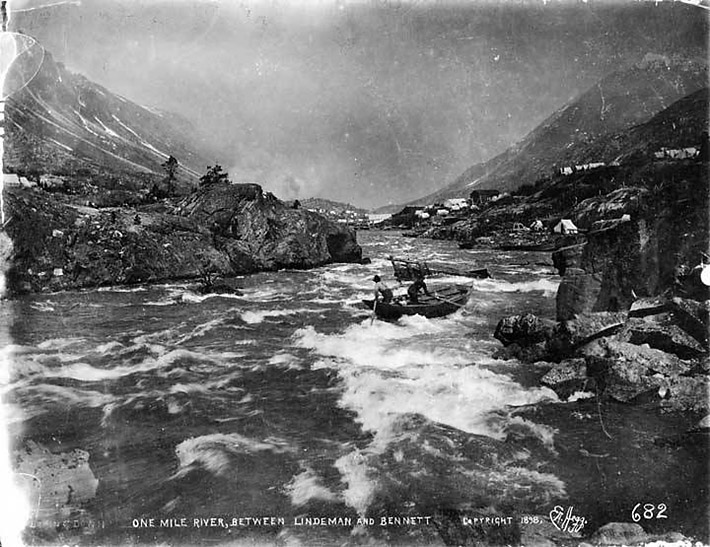

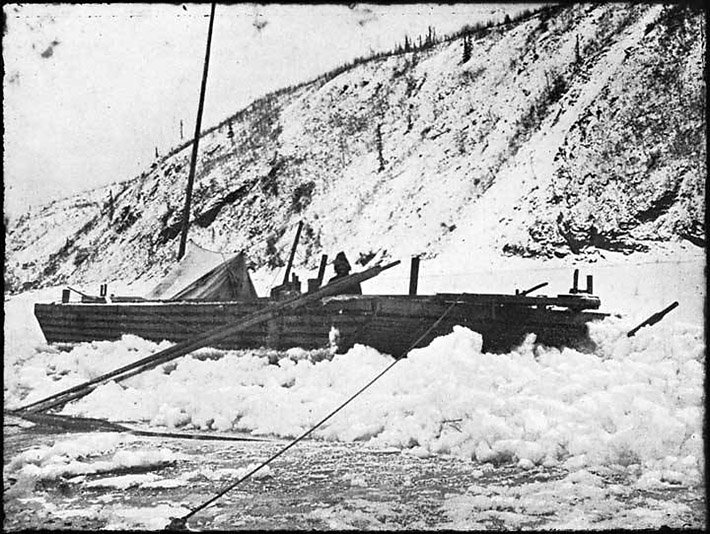

Klondike: Crossing the Chilkoot Trail Pass

Access to the goldfields was difficult; two main routes were available: by water, from the Pacific Coast to the mouth of the Yukon in Alaska, thence upstream to Dawson City for a total trip distance of 4,700 miles; overland from a southeast Alaska port (Skagway) to reach the mouth of the Yukon River via one of two trails established a decade earlier, Chilkoot or White Pass, and sail 500 miles downstream to the Klondike area. In both cases, travel on the river was treacherous because of winter icing, narrow canyons and difficult rapids. Only few prospectors reached the Dawson City on the steamboats - it was already too late and the boats were trapped in the ice on Yukon river. Also many prospectors on the trails spent brute winter trapped on the river or near the lakes.

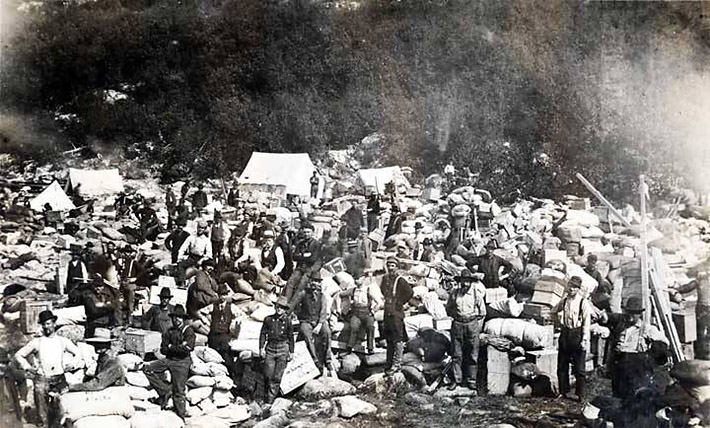

Since the Northwest Mounted Police (NWMP) was the de facto administrator of remote regions of Canada, it was able to compel all prospective Yukon Territory travelers to bring with them a year's supply of food (520 kg) to prevent starvation. Adding to the misery, other normal equipment could add another 500 kg in weight. Transporting supplies was not manageable without the use of draft animals, and horses sold for over $19,000 or rented for $1,100 (current USD) per day.

The definitive border between US and Canadian territory in southeast Alaska had not been determined with certainty after the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867. The flood of prospectors into the Yukon from an uncertain border area in Alaska became a sensitive issue between the US and Canada, with the result that mutual concessions were made: Canada freely allowed the Americans to pass, and the US allowed British ships to land cargo near Skagway. The NWMP did set up customs stations at the easily-managed crossings. At these border posts, it was able to enforce the food requirement cited above, as well as check for illegal weapons, bar criminal entry, and collect a 25% duty on imported supplies and equipment.

Overland travel conditions were arduous and temperatures extreme, dropping to -50o C. In spite of the controls imposed by NWMP, hundreds died en route from disease, starvation and cold. More often than not, travelers were stopped in their tracks, forced to abandon their supplies and turn back. Many ended up stranded for months along impromptu settlements along the river. Of the 100,000 who set out for the Klondike initially, only about 30,000 reached the area.

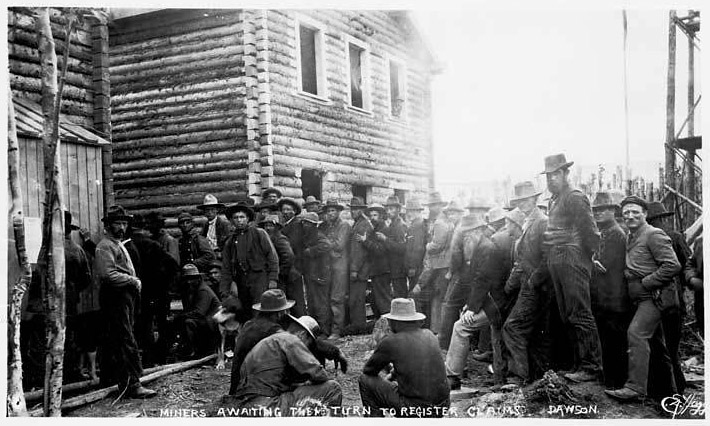

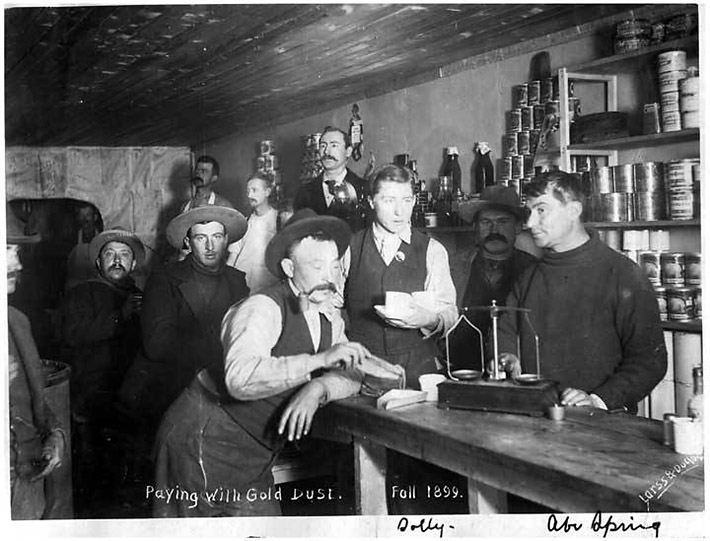

Entrepreneurs took advantage of the wave of humanity and established townsites along the route to supply the crowds with essentials, culminating in the establishment of Dawson City, the terminus of the expedition. The town population swelled from 500 in 1896 to 30,000 two years later. Conditions in Dawson City were typical of 19th century frontier boom towns - extremely expensive, unsanitary, and prone to fires.

The numbers tell a story of brutal winnowing of the aspirants to wealth: of 100,000 souls who ventured north, 30-40,000 reached Dawson City; of those, 15-20,000 worked at being prospectors; of those, 4,000 held valid mining claims; of those, only a few hundred became wealthy. Most of the success went to the earliest arrivals, or older residents who had laid claim to potentially mineralized creeks tributary to the Yukon River.

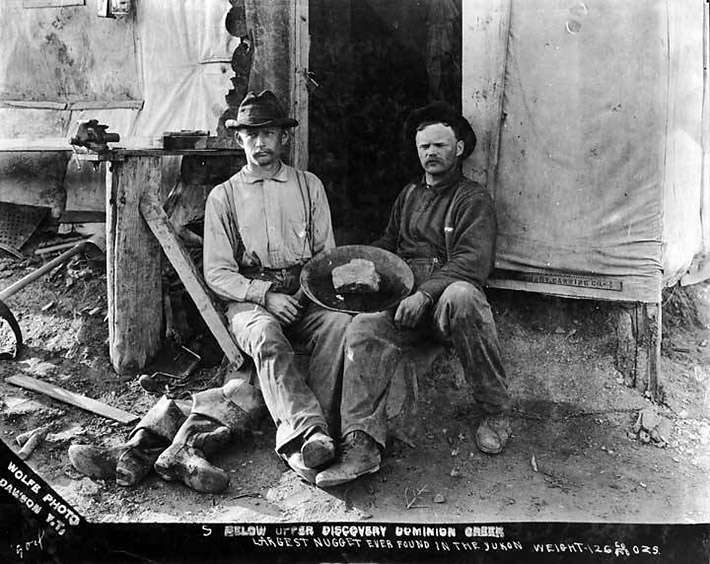

The geologic setting of the gold was simple in the sense that the gold originated in veins in volcanic rock; miners initially assumed that most of the gold would be found in eroded materials (placer accumulations) deposited along the riverbed of the Yukon and tributaries, and that the accumulations would be found within a foot or so of the bedrock surface. What was not realized at first was that the depth of sediment accumulation along the river could be as much as 30 feet, creating several pay streaks somewhat above bedrock, or that there had been several periods of downcutting by the river which had left stranded benches of placer gold higher up on mountainsides. This meant that prospecting in the Yukon valley floor required a great deal of physical excavation to hunt for the placers, and an equally large investment in trolling for the bench gold on hillsides. Prediction was not much use.

The icy conditions in the Yukon required miners to overcome the problem of permafrost. Heavy mining equipment, including dredges, was inappropriate for the physical environment, so miners resorted to building fires to soften the ground to a depth of a foot to allow digging it up to check for gold. This process could be repeated indefinitely, laterally and with increasing depth, but the deepening action generally melted permafrost and caused the walls of the current hole to collapse. Dirt excavated in the winter often froze before it could be adequately screened for gold, so miners were forced to wait until summer to fully evaluate their collected dirt.

Klondike: Excavations in Alluvium

A technology called steam thawing, using a furnace to pump steam underground was tried on a small scale, but proved cumbersome to manage because of the requirement for additional equipment.

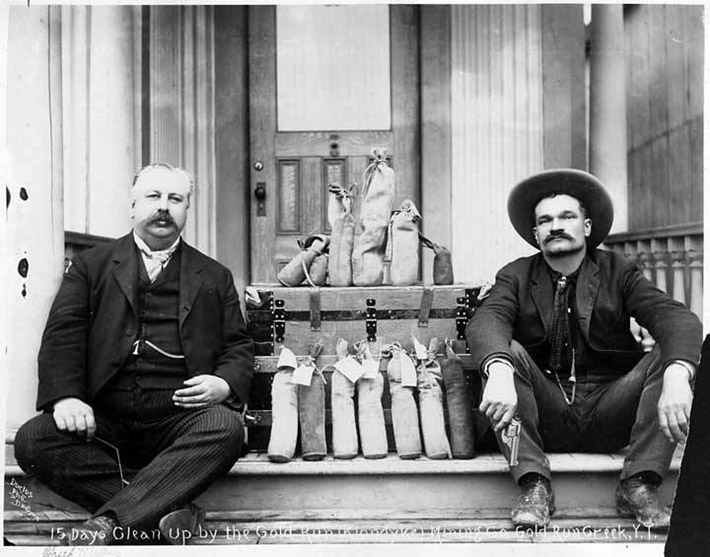

Summertime gold-separation operations involved the construction of rectangular sluice boxes fed by locally stored water or piping from creeks. The availability of flowing water limited these sluicing operations to dirt collected on the valley floor; water could not be pumped high enough to wash the bench gold zones found on the hillsides, so miners were forced to rely on cumbersome wooden rocking cradles to achieve separation.

Klondike: All in a Day's Work

The rich grade of pay streaks in the alluvial placers fully justified the operating costs to bring it to the surface. Contemporary estimates, is USD, claim that the likely cost for wood to melt the ground would be $1.2 million; dam construction, $800,000; ditches, $1.2 million; sluice boxes, $480,000. In other words, $3.7 million in costs for a return of hundreds of millions.

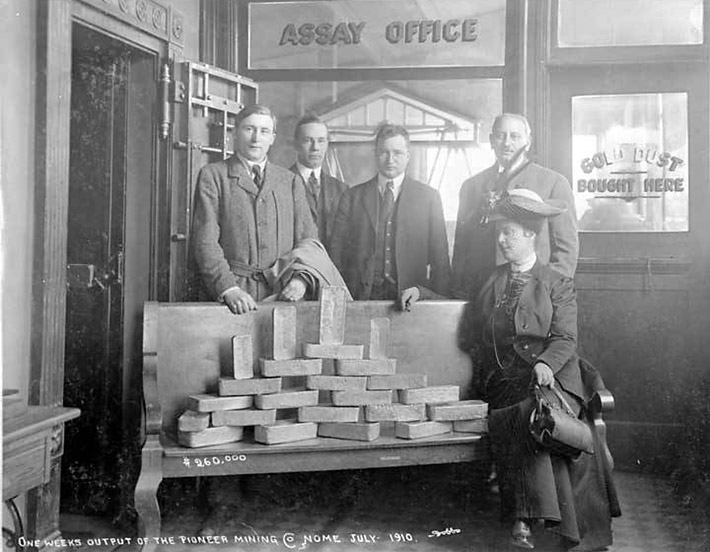

Cumulative gold production from 1885 to the present is estimated at 12.5 million ounces, which includes a rapid increase from 1897 to 1903, followed by an equally rapid drop to 1908, followed by an intermittent production of 100,000 ounces per year from small operations.

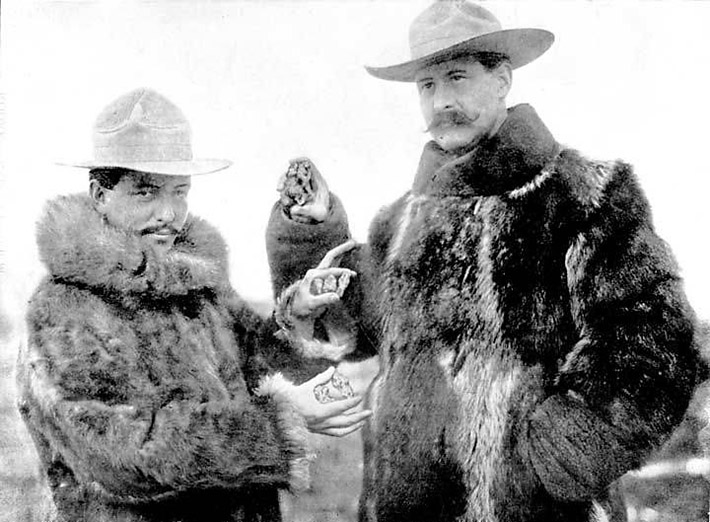

The Nome Discovery

Two years after the opening of the Klondike, another improbable discovery of gold ignited a second wave of migration to Nome, a settlement on the west coast of Alaska, at the mouth of the Snake River, facing the Bering Sea. As in the Yukon, there had been a continuous Native (Inuit) presence with little recognition of gold and more interest in whaling and fur trading. The discovery was made by so called Three Lucky Swedes - Jafet Lindeberg, Erik Lindblom and John Brynteson.

News of the discovery in the fall of 1898 did not reach the outside world until winter, and by 1899 about 10,000 new arrivals flooded into Nome, a goodly number of them having made their way northwest from the Klondike.

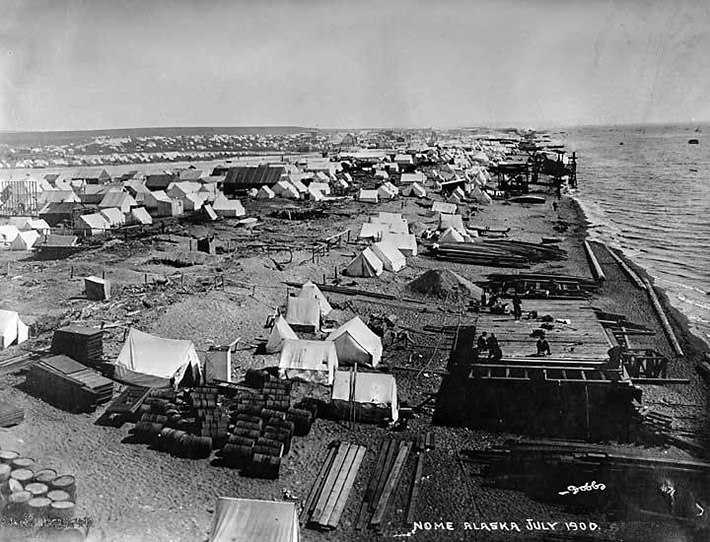

Nome: Shoreline Mining

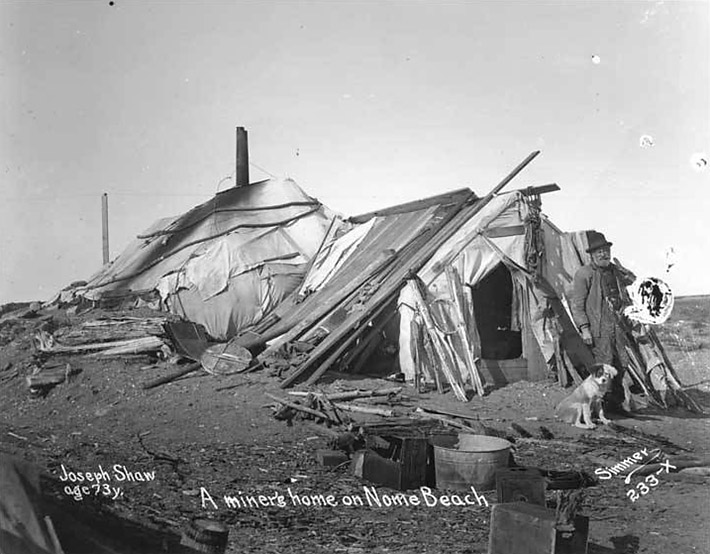

Mineralization at Nome was far easier to discover and mine, because the gold was simply an accumulation of coarse grains along a long stretch of beach sand, so much so that a 30-mile-long tent city occupied the beach by 1900.

Nome: Tent City

Whereas the regulation of mining activity in the Klondike under Canadian administration had proceeded in an orderly fashion, the situation in Alaska was a free-for-all which degenerated into a series of corrupt deals, influence peddling and bribery. Initial claims had been upheld as valid, but many instances of claim-jumping (overstaking existing claims) followed, and a corrupt American Congressman, in concert with a corrupt local judge, managed to use the invalid claims to take over legitimate ones.

Because the shoreline of the Bering Sea was more accessible, Nome witnessed a rapid transition in the style of mining, and the amount of heavy equipment brought to bear on the problem. Remember that at Klondike, gold extraction was a drawn-out process of manually heating areas of soil and painstakingly digging through the melted permafrost. At Nome, mechanization of the heating, digging and soil processing proceeded more rapidly (although still limited to summer months). Efficiency was less important than the ability process large volumes of dirt. The result was a much more rapid and thorough extraction of gold, even in the nearby creeks flowing down to the shoreline.

Just as had happened at Klondike, continued exploration revealed the existence of higher stranded shelves of gold accumulations from older shorelines, but the volume was not nearly enough to extend the life of the district, and the mining activity declined significantly by 1909. Total estimated production over the 10 or so years of activity was 3.6 million ounces.

The Aftermath

Economically, the exhaustion of the gold camps took its toll on the people and places central to the drama:

- Most of the miner wannabes were unsuccessful, and ended up working as laborers on site, or returned home.

- The ambitious townspeople - owners of service and supply businesses - prospered during the boom and then lost their newfound wealth as the mining districts were abandoned.

- The indigenous Natives at first secured work as guides, trappers and packers, but succumbed to renewed poverty and smallpox, and witnessed much degradation of their natural environment due to the frenetic mining activity.

- The townsite of Skagway - the former jumping-off point for the Yukon interior - shrank to a shell of its former self, now functioning as a cruise-ship tourist stop.

- The main access routes - Chilkoot Trail and White Pass Trail - now survive as a popular hiking trail and restored tourist railway, respectively.

- The destination city of Dawson retains a tourist industry with a population hovering around 1,000.

- The destination city of Nome fared slightly better, with a surviving population of about 2,500.

Culturally, the combined gold rushes left a permanent imprint on the American psyche as a symbol of the romantic quest for success within the reach of Everyman. The event was memorialized in numerous books and films, and formed the framework for many of the Jack London novels of the Far North. Photographers routinely produced iconic photographs. The idea of striking it rich resonated with many Americans, and accounted for the easy abandonment of home and hearth to strike out in new directions.

In 1893, Frederick Jackson Turner of the University of Wisconsin rose to speak before the American Historical Association meeting during the Chicago World's Fair. He delivered what became one of the landmark papers in Americans' understanding of themselves.

In the paper, The Significance of the Frontier in American History, Turner argued that the completion of the westward expansion of the US and the final settlement of the frontier directly accounted for the rugged American character which had produced a new type of citizen; one who had received strength and individuality from the savage wilderness and acquired the power to tame the wild. Successive generations of westward migrants abandoned useless European attitudes and invented practical solutions to new problems, leading to a culture of informality, democracy and initiative.

Jackson was speaking at the time of the linking of the two coasts by the transcontinental railroad, the resolution of the Civil War, and the pioneer infilling of the unpopulated Western states. If he had waited until 1897, when the first Klondikers embarked for the Yukon, he could have been speaking of them as well.

Recent Gold Mining

Both Klondike and Nome areas are still productive regarding gold. Lonely prospectors, smyll teams and large companies still test their luck and mining skills with various results. There are still bonanzas to be found and impressive amount of paydirt left. There even exist several reality shows about gold mining - the famous Gold Rush Alaska, Bering Sea Gold and Yukon Gold.

Acknowledgements

Author and editor highly appreciate help of the Alaska State Library, which kindly provided the permission to use the photos from their digital archive. Visiting ASL extensive photo archive is highly recommended for all interested in history of Alaska and Yukon. Special thanks to Sandra Johnston from ASL for the help with the papers and questions.

Comments