Ankerite – Mineral Properties, Photos and Occurrence

Ankerite is interesting and surprisingly uncommon carbonate, mostly limited to metasomatic rocks and hydrothermal veins. It can form outstanding crystals and clusters.

Crystal Structure of Ankerite

Ankerite is a calcium-iron carbonate with ideal chemical formula CaFe(CO3)2. Ankerite is a member of dolomite group and often contains significant amount of dolomite (Mg) and kutnohorite (Mn) component. Pure ankerite was never identified in nature, it always contains impurities.

Modern analytical work revealed that many ankerite specimens are actually Fe-rich (ferrous) dolomite. The true ankerite is quite uncommon. Even the specimens from the same locality can vary between Fe-rich dolomite and Mg-rich ankerite.

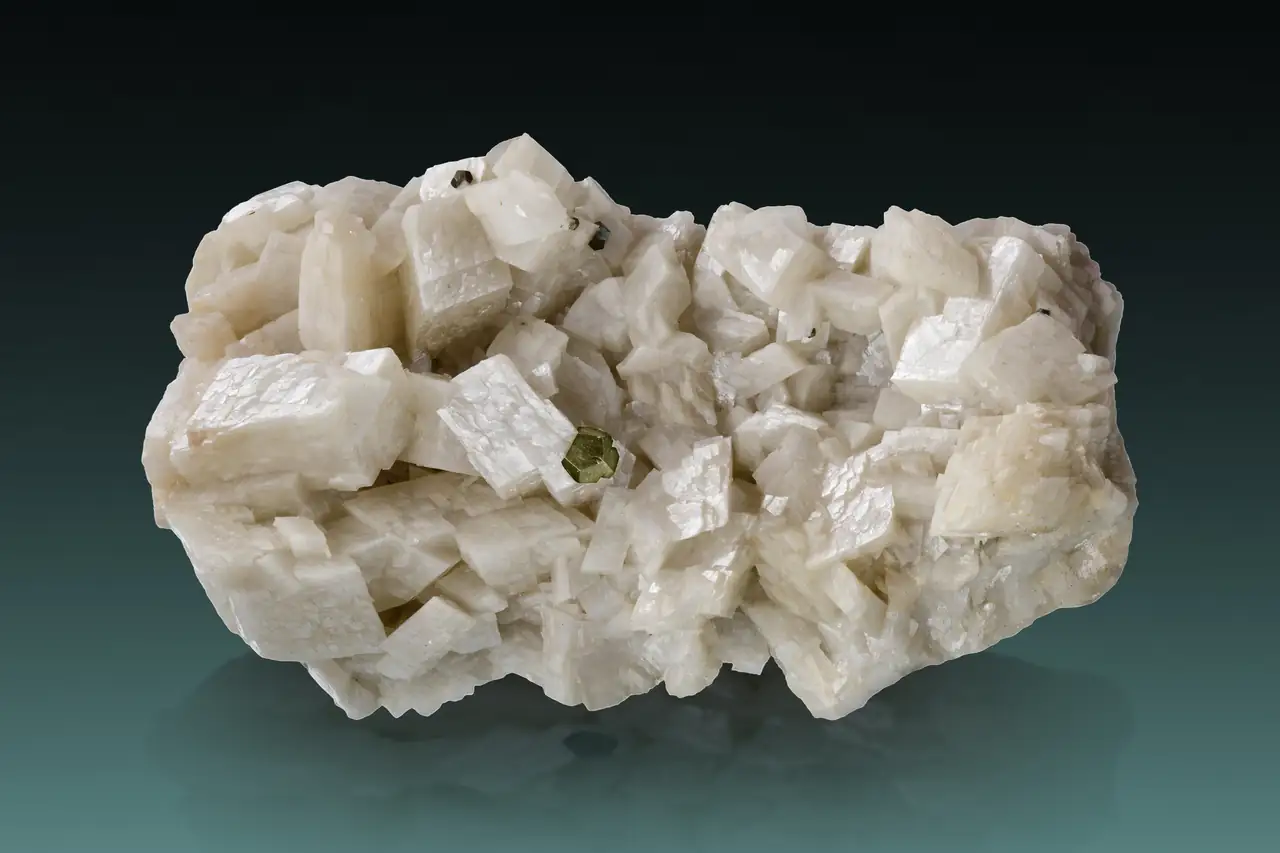

Ankerite crystallizes in the trigonal system, usually forming simple rhombohedron shaped crystals. Ankerite may exhibit simple twins on {0001}, {1010} or {1120}. Crystals often display curved faces, and may occur as columnar, tabular, granular or massive specimens.

Physical Properties of Ankerite

Ankerite colors normally include white, grey, brown, yellow or reddish to yellowish brown. Typical feature is slow color change when exposed to surface conditions. Fresh ankerite is pearly white and it turns to brown or rusty color after some time.

Cleavage is perfect on {1011}. It is transparent to translucent in thin pieces. Its luster is vitreous to pearly. Its fracture is subconchoidal to hackly; the mineral is brittle. Its hardness is 3.5-4.0. Its streak is white, and its density is 2.93-3.10 g/cm3.

Associated minerals

Ankerite often occurs on hydrothermal/metasomatic deposits together with dolomite, siderite, baryte, quartz, fluorite, and ore minerals like tetrahedrite, chalcopyrite and pyrite.

Naming and Discovery

Wilhelm von Haidinger (1795-1871) was a dedicated, prolific Austrian mineralogist who specialized in unraveling the possible geochemical transformations of the various carbonate minerals, focusing in particular on the phenomenon of pseudomorphism among carbonates.

Early in his career, he identified ankerite as an iron-magnesium carbonate, and named it after Matthias Joseph Anker (1771-1843), an older Austrian contemporary who was instrumental in implementing the Mohs hardness system in organizing mineral collections.

Similar minerals

Fresh pale colored ankerite looks exactly like dolomite or magnesite, while the surface-oxidized specimens are brown and can’t be distinguished from siderite. Precise identification requires analytical tools.

Other pale colored carbonates may look very similar to ankerite too, but calcite has different luster and rhodochrosite or kutnohorite usually have pale to saturated pink color.

Chunks of massive pale colored baryte may look very similar to ankerite too.

Ankerite Origin

Large amount of Fe-rich dolomite to Mg-rich ankerite may be present in some biochemical and chemical sedimentary rocks, generally classified as dolostones.

Ankerite can occur as a common gangue mineral in a variety of settings where low-temperature alteration of carbonates creates new authigenic or diagenetic minerals, or in hydrothermal systems penetrating carbonate rocks. More generally, low-grade metamorphosed ironstones and sedimentary banded iron formations (BIF) are frequent repositories of large quantities of accessory ankerite.

Ankerite also occurs in some iron-rich carbonatites.

Uses of Ankerite

Ankerite has only limited industrial use, mostly in special construction or refractory materials. It might be used as very poor iron ore in the past, together with siderite.

Occurrence of Ankerite

Ankerite is known from many localities, but only some have yielded fine crystals:

European localities include Brownley Hill Mine, Cumbria and in the Oldham area, Lancashire in England; Regia Mine, Bellmunt del Priorat, Catalonia in Spain; Brosso mine, northwest of Ivrea, Torino in Italy. Famous are Austrian sites in Styria, from the Erzberg, Eisenerz, and at Gollrad; Steiermark.

In the US, at the Jeffrey Quarry, near Little Rock, Pulaski Co., Arkansas, and from the Eagle Mine, Gilman District, Eagle County, and many other places in Colorado.

Other notable localities are Muzo, Boyaca Province in Colombia; mines at Dundas, Western Tasmania in Australia or Tui Mine, North Island in New Zealand.

Additionally, of the many worldwide occurrences of sedimentary iron formation, several are cited as source material for the study of ankerite: the Mesabi Range in Minnesota (US); the Sokoman Iron Formation, Howells Rover Area, Quebec (Canada); and the Dales Gorge Member, Hamersley Group (Western Australia).

References

- Chai L., Navrotsky A. (1996): Synthesis, characterization, and energetics of solid solution along the dolomite-ankerite join, and implications for the stability of ordered CaFe(CO3)2. American Mineralogist, 81(9-10), 1141-1147.

- Hendry J. P., Wilkinson M., Fallick A. E., Haszeldine R. S. (2000): Ankerite cementation in deeply buried Jurassic sandstone reservoirs of the central North Sea. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 70(1), 227-239.

- Reeder R. J., Dollase, W. A. (1989): Structural variation in the dolomite-ankerite solid-solution series; an X-ray, Mössbauer, and TEM study. American Mineralogist, 74(9-10), 1159-1167.

- Ross N. L., Reeder R. J. (1992): High-pressure structural study of dolomite and ankerite. American Mineralogist, 77(3-4), 412-421

- Thompson R., Smith P., Gibson S. A., Mattey D., Dickin A. (2002): Ankerite carbonatite from Swartbooisdrif, Namibia: the first evidence for magmatic ferrocarbonatite. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 143, 377-396.

Comments