Cassiterite - the Tin Ore Mineral Overview

Cassiterite constitutes the chief ore of tin, as well as highly aesthetic and popular mineral specimen. Tin was a foundation of the beginning of metal smelting in the early Bronze Age and still constitutes one of the core materials of modern technology.

Cassiterite is dense, resistant to abrasion, and stable in the surface Earth environment. The result is that tin can be mined from its primary environment (granitic vein systems) and its secondary environment (erosional placer accumulations in rivers and beach sands).

There are three possible origins of the name cassiterite.

- from the Phoenician Cassiterid, referring to the ancient sources of tin in Ireland and Britain

- from the Greek kasseritos (tin)

- or from the name of an ethnic group originating in west and central Iran, the Kassites.

Crystal Structure of Cassiterite

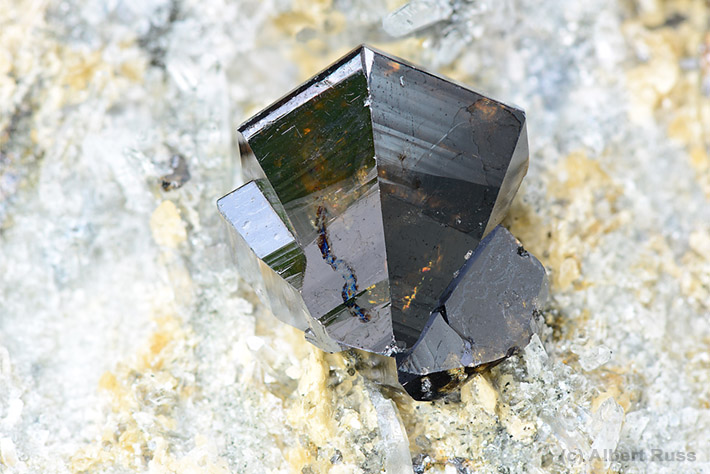

Cassiterite is a simple tin dioxide, SnO2. It is a member of the tetragonal system, appearing as various ditetragonal dipyramids. Its expression may be prismatic, or occur as fibrous botryoidal crusts with radial symmetry. Aggregates include massive concretionary or grainy masses. Cassiterite has the same structure as rutile (TiO2) and often contains a certain amount of Fe.

Twinning in specimens is very common, with the twins bent at a 60o angle called an elbow twin. Cassiterite very often forms as repeated twins or intergrowth twins.

Physical Properties of Cassiterite

Colors include black, brownish-black, reddish brown, red, yellow, gray or white. Transparency is possible if light-colored. Incident light may be split into two discrete colors (dichroism), including yellows, greens, reds or browns.

Cleavage on {100} is imperfect; on {110}, indistinct; on {111} or {011}, with indistinct partings. Luster is adamantine to metallic, but greasy on fractures. Fracture is subconchoidal to uneven. Its hardness is consistently high, 6.0-7.0, with a white to brownish-white streak and a density of 6.98-7.10.

Varietes

Acicular forms of cassiterite are called needle tin. Stream tin describes water-worn pebbles of cassiterite from placers. Wood tin is a botryoidal cassiterite exhibiting concentric banding.

Origin

Cassiterite occurs in two primary environments: as a primary magmatic mineral in tin-bearing granites and pegmatites and as alluvial (placer) deposits, where the resistant grains accumulate as well-rounded water-worn crystals.

Some granites are enriched in Sn and their intrusions may contain significant amount of cassiterite in the upper parts of the granite body. These deposits usually contain significant amount of Sn, W, F, B and Li and are known as greisens. The origin of greisen deposits is very complex, but essentially there are 3 main features (not all must be developed): 1) fine grained tin-bearing rock, mostly in the uppermost part of the granite intrusion, 2) a massive quartz stock, and 3) a network of mineralized quartz veins radiating from the granite and quartz stock. Cassiterite is often present in all of them.

All these features are developed when the highly water- and volatile-rich melt in the upper part of the granite body cools down and the water and volatiles are expelled from the melt in the form of highly aggressive and reactive fluids. These fluids react with the solid granite and form fine grained greisens or spread along structures and precipitate as stocks or veins. While fine-grained greisen is easy for miners to exploit, the quartz stock and veins often contain vugs with high quality cassiterite crystals.

Cassiterite is often associated with quartz, muscovite, various Li-micas, wolframite, fluorite, tourmaline, topaz, fluorapatite, molybdenite, chalcopyrite and arsenopyrite. Rare minerals like native bismuth, bismuthinite, triplite and many other minerals are less frequently present.

Applications

Cassiterite is the major ore of tin. Its fundamental characteristics are: non-magnetic, non-combustible, corrosion-resistant, lightweight, durable, soft, ductile, malleable, expensive and low-maintenance.

Tin finds major applications as an alloy or coating in diverse products. Alloyed with copper, it produces bronze. The bronze was the main metal for mankind for several millennia - known as the Bronze Age. After discovery and use of native copper, the use of bronze emerged around 3000 B.C. in Middle East and spread to Europe and China around 2000 B.C. Creating bronze was a core technology of many ancient civilizations - including ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome - until the discovery of iron smelting.

Tin coating of iron and steel can be turned to a variety of uses. Coatings used to be applied manually in the 19th century by dipping the object in molten tin; since the beginning of the 20th century, electroplating (passing an electric current through the metal) has replaced manual coating. The main advantages of coating are creating an object that will take a high polish, and establishing resistance to corrosion.

Historically, pure tin was dedicated to small objects, such as lantern and candle shields, plates, bowls, wall sconces and mirror frames. Tin-coated objects included waterproof roofing materials, shingles, wall coverings to mimic masonry, flashing (roof-mounted water barriers), gutters, downspouts, door and window fire protection sheets, and ornamental building items.

Tinplated objects will resist chemical corrosion to moisture, oxygen, and hydrogen & sulfide gases, but will succumb to any asphaltic or bituminous materials, including paints containing the preceding, as well as acids, graphite or aluminum.

Tinplated objects will suffer galvanic (electrically-induced) corrosion if copper comes in contact with iron, steel, aluminum, or other mixed-metal tin objects.

Occurence of Cassiterite

Cornwall (England) is the best known and most familiar site of historic vein and placer mining, including use of extensive hydraulic mining methods. Bolivia is a current center of vein tin production. The principal sites of tin placer mining are in the South Pacific (Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia), Somalia and Russia. As a general rule, placer deposits will yield specimen-quality cassiterite sparingly, owing to the erosional origin of the deposit.

Europe

England: Owing to its historic importance, it is worth dwelling a bit on the occurrences in Cornwall. Cornwall is the southwestern tip of England, famous for tin granites intruding Devonian rocks, and for the Cornish miner's favorite dish, the pasty, a baked folded pastry wrap filled with meat, potato, turnip and onion). The pasty has spread world-wide owing to the emigration of Cornish miners. Detailed geology of Cornwall are is available here.

The Cornwall District is a historically significant site because it has the highest concentration of early successful tin mining. The earliest documented accounts of tin mining there date to 1305-1306, when county records reflect active shipping of tin to the county seat of Truro. Among its historic engineering firsts are the site of the world's first house illuminated by gas (1792), the development of an effective steam engine (1801), and invention of the safety fuse (1830). The safety fuse works by incorporating a uniform stream of gunpowder into a braided rope; the rope burned at a constant rate of 30 seconds per foot, enabling miners to prepare a fuse of the correct length to create a detonation with the desired safety interval. In 1848 a monumental engineering project, the Great County Adit, drained deeper workings through a system of adits.

Tin mineralization at Cornwall is the end result of a series of Permian (295-270 Ma) granite intrusions occurring as apophyses of a large complex of batholiths amounting to 68,000 km3 of intrusive rock. The individual stocks intrude Devonian slates. One such cupola, Cligga Head on the north coast of Cornwall, has been studied in detail, and the descriptive information provided below is a useful snapshot of the global batholithic complex and the spatial control of mineralization.

At Cligga Head, the granite is an outlying cupola of the Hemerdon Ball granite intruding Devonian slates. The granite itself is notably enriched in the volatile elements (Sn, Li, B, F) responsible for evolving a fluid-rich mineralizing system rich in tourmaline. The granite is regionally zoned, with the western portion of the axis of the batholith enriched in tin-tungsten-copper-zinc and the eastern portion enriched in arsenic, antimony, fluorine and barium. Discrete zonation is also evident in the distribution of lead and silver, which is restricted to south-facing embayments in the massif. Mine production records confirm the observations: All significant tungsten production comes from the western axis of the batholith, within 700 m of the granite-slate contact; 90 % of all tin-copper-arsenic production from within 1500 m of the contact, and 80 % of lead and silver more than 1500 m from the contact.

At Cornwall, the single largest past and present producer has been the Drakelands (formerly Hemerdon) Mine, which has been in intermittent operation since 1867. The quartz- and greisen- (hydrothermally altered-granite) mineralization itself occurs in shears and sheeted vein systems in the granite and slates, from the surface down to a depth of 400 m.

The deposit is large, amounting to over 40,000 tons of tin and 300,000 tons of tungsten; as late as 2000, the deposit was ranked as the 4th largest tin-tungsten deposit in the world. Recent exploration and modeling of the deposit, coupled with marked increases in the world price for tungsten, will catapult the mine into first place if projected expansion plans are carried out.

The most prominent districts for worthwhile specimens are Redruth-St. Day and St. Agnes. The Redruth occurrence lay in the Great Flat Lode, a gently-dipping (-350) sheet of high-grade tin mineralization 6 km long. The St. Day occurrences were successfully accessed (1748) by the Great County Adits. St. Agnes is now part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

La Villeder and Le Roc Saint-André, in Brittany, France are both historic sites with infrequent production.

Panasquieira in Castelo Branco, Portugal is better known as a tungsten production site. The cassiterite mineralization is located in a contact metamorphic aureole in Precambrian greywackes and shales surrounding the felsic Panasquieira Granite. The site has yielded a large number of diverse, high-quality specimens, including apatites. The industrial-scale mining operations damage good specimens, and mine managements have imposed harsh penalties on working miners who attempt to salvage and remove them from the property. Similarly, visiting old mine workings for collecting is also illegal.

Czech Republic: Classic localities in Bohemia are Krásno, Horní Slavkov and Krupka. The earliest references to tin mining in these areas date to reports of exports by an Arab merchant in 965-966 A.D. By the mid 14th century, tin mining was well established enough to allow Krasno and Horni Slavkov to be designated as mining towns. The mineralization is the result of small Paleozoic stocks intruding a complex of older granite batholiths and metamorphosed sediments. The tin vein systems occur along the upper and side contacts of these stocks, somewhat controlled by NW-SE fault zones. Horni Slavkov and Krasno produced excellent cassiterite crystals and intergrowth twins up to fist size. There were several mines in the area; the best known is the Huber Stock, located between these two towns. Krupka is known for the excellent clusters of world class cassiterite crystals. However, many of Krupka specimens were originally coated with hard dickite clay, which had to be removed by hydrofluoric acid.

Germany: Similar occurrences on the Saxony side of the Czech-German border are found in a similar geological deposit (Ehrenfriedersdorf, Altenberg, Sauberg and Sadisdorf, Erzgebirge).

South America

Some of the finest cassiterite specimens were recently produced in Bolivia. Locations where lustrous and sometimes transparent crystals come from include Huanuni, Dalence Province, Oruro Department; and Llallagua, Potosi Department. The Huanuni deposits are explained as cassiterite precipitates from a hot saline magmatic fluid injected into heated low-salinity meteoric water. The Llallagua occurrences are genetically related to granite intrusives invading the surrounding Paleozoic sediments.

Some of the Brazilian gem pegmatites in Minas Gerais have produced perfect cassiterite specimens, especially Linópolis, in the Doce Valley.

Asia

China: New production is coming from historically old sites, going as far back as the 13th century. In Sichuan Province, Xue Bao Diang produces cassiterite from quartz-sulfide veinlets, and shiny black crystals come from Mt. Xuebaoding, Pingwu. Ximeng, in the Langcang Jiang river area, Yunnan Province, accounts for a good supply of transparent brown crystals (The Langcang Jiang is the Chinese name for the upper reaches of the Mekong River, which flows through China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam).

Similar black crystals are reported from the Yaogangxian Mine, Hunan Province; three vein swarms, zoned vertically and horizontally, occur at the western and northern contact zones of a variety of granites intruding Cambro-Devonian sediments.

At Dayu, Jiangxi Province, a greisen-rich stockwork developed in Jurassic granites has intruded overlying Cambrian sediments with a highly varied suite of minerals and alteration characterized by multistage pulses of mineralization in a fracture-controlled environment.

Russia: Excellent lustrous crystals come from Merekski and Lultin Mine in the Russian Far East.

Australia

Australia: The inactive Aberfoyle Mine in Tasmania, last worked in the 1970s, contains large waste dumps which continue to supply transparent brown crystals. The Elsmore Mine, New South Wales, was an early source of alluvial cassiterite occurring in large crystals; discovered in 1871, the site was the first commercial tin mine in Australia.

North and Central America

United States: Cassiterite is not common in the U.S. Sporadic production is recorded from a few gem bearing pegmatites, mostly in New England: Greenwood, Oxford Co., Maine; Amelia, Amelia Co., Virginia; and Taylor Creek, Sierra Co., New Mexico.

Mexico: An unspecified locality in Durango has yielded quality reniform and botryoidal wood tin.

CONFLICT MINERAL SITES IN AFRICA

(Democratic Republic of) Congo

Congo is among the top 5 producers of tungsten worldwide, but is better known for its involvement as a supplier of conflict minerals than collectible specimens. Conflict minerals is a legally-defined set of minerals - columbite, tantalite, cassiterite, gold, wolframite or any of their derivatives - whose sale is being used to finance conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Cassiterite mining is concentrated in the eastern part of the country, and continued sale of the product, along with wolframite, to global supply chains is blamed for an ongoing monthly death toll of 45,000 people and an aggregate total of 5.5 million deaths since 1994. In response to legislation enacted in the US in 2012 (Dodd-Frank Law), publicly traded companies using suspect minerals from Africa are required to perform due diligence to create self-imposed obstacles to such purchases and be able to certify the legitimacy of their supply chain. Unfortunately, the developed world's insatiable appetite for electronic devices undermines such preventive activity, no matter how well-intentioned.

Rwanda

Rwanda has a slowly increasing level of production of cassiterite, amounting to 1,200 tons recently from 40 producers. It has adopted certification programs, like those intended to apply to Congo, to assure the ethical legitimacy of product it sells to the outside world.

Comments