Cerussite (lead carbonate) - Mineral Properties and Occurence

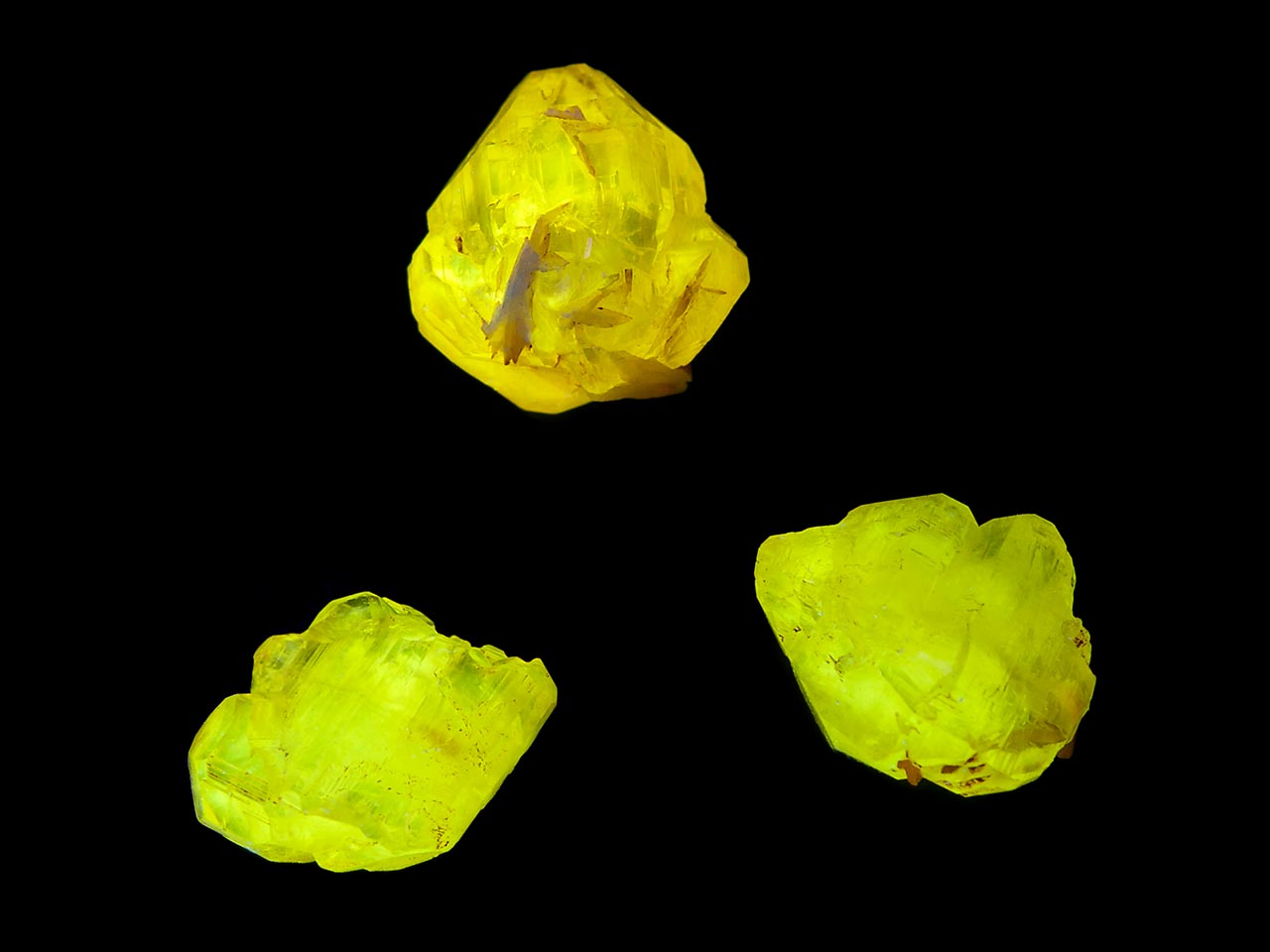

Cerussite is a popular mineral specimen because of its nice crystals, bizzare complex twins and bright yellow fluorescence. It is a characteristic oxidation product of the most common lead sulfide, galena.

Crystal Structure of Cerussite

Cerussite is a lead carbonate mineral, PbCO3, which forms orthorhombic crystals. Cerussite belongs to the aragonite group of carbonates - together with aragonite (CaCO3), strontianite (SrCO3) and witherite (BaCO3).

Cerussite structure can accomodate limited amount of Ca, Ba and Sr.

Its crystal habit occurs in one of three principal modes: small flat thin plates, prismatic crystals and tabular crystals. Often three crystals are twinned on two faces of a prism, resulting in a variety of unusual shapes, including v-shaped twins, stars, hearts and sixlings (six interconnected crystals joined at the base, forming a six-rayed stellate group with individual crystals intersecting at 60o angles). Another unusual form is the wheat sheaf, compact bundles of crystals radiating thicker at the top and bottom and unusually narrow in the center. It also forms as fibrous, acicular, reticulated, coxcomb, massive or granular masses.

Physical Properties of Cerussite

Cerussite is colorless to white, with greenish, bluish or grayish tints. It is virtually insoluble in water, but dissolves in dilute nitric acid and effervesces in other dilute acids. Especially thin needle-like crystals and complex twins - including famous snowflakes - may be fragile.

Cerussite is translucent to transparent. Its luster is adamantine, vitreous, greasy or resinous. Fibrous varieties are described as silky. Its fracture is brittle to conchoidal. Its hardness is 3.0-3.75, its streak white and its density is 6.53-6.57. Cleavage on [110] and [021] is good.

Cerussite usually fluoresce cream-white to yellow under shortwave UV light, and yellow under longwave UV light.

Similar Minerals

Aragonite (CaCO3) is lighter in weight, less brilliant in luster, and strongly effervesces in hydrochloric acid.

Anglesite (PbSO4) doesn't effervesce at all in hydrochloric acid or dissolve in nitric acid, and never forms twinned crystals. Otherwise, it is very difficult to distinguish.

Phosgenite [(PbCl)2CO3; lead chlorocarbonate] is softer, occurs in different crystal forms, and fluoresces bright orange.

Hemimorphite [(Zn4(Si2O7)(OH)2.H2O; calamine] is harder and not as dense.

Associated Minerals

The usual common companions of cerussite are primary sulfides galena and sphalerite and gangue minerals like quartz, baryte and calcite. It is often associated with many secondary minerals like anglesite, azurite, malachite, phosgenite, pyromorphite and smithsonite.

Naming and Discovery

The source of the name cerussite is the Latin, cerussa (white lead). It was originally named cerussa nativa in 1565 by Conrad Gessner, a Swiss naturalist and pioneer in zoology; renamed cuise in 1832 by Francois Sulpice Beudant, a French mineralogist; and renamed cerussite in 1845 by W. Haidinger, an Austrian mineralogist and assistant to Frederic Mohs.

Historical Names

Early miners referred to it as lead-spar and white-lead-ore.

Varietal names

Iglesiasite, from Iglesias in Sardinia, is a variety containing 7 % Zn. Cation substitutions of Ag and Cr replacing Pb are also possible in unnamed varieties.

Origin of Cerussite

Cerussite is a common product of surface oxidation of primary lead sulfide minerals, especially galena. It usually appears in the upper part of iron caps (gossan), because formation of cerussite requires influx of oxygen and CO2.

Applications

There is only one primary use of cerussite - as a lead ore, and a minor secondary one, as an occasionally faceted gemstone. As an ore, lead is generally used in the manufacture of batteries, plumbing, ammunition, sound absorbers, X-ray and radiation shields, paint pigment, glass and insecticides.

Lead and its related compounds were misused for generations before its intrinsic hazards were fully appreciated. Formerly, the variety called white lead was a principal ingredient in lead paints and facial cosmetics.

The use of white lead in paint began in the U.S. in the Colonial period and continued uninterrupted until the early 20th century, peaking in the decade of the 1920s. As far back as 1904, one of the leading U.S. paint manufacturers, Sherwin-Williams, warned of the dangers of airborne lead particles from flaking paint. Its use was selectively prohibited in some cities in the 1950s in belated recognition of the fact that children eating peeling paint chips acquired a dangerous body-burden of lead. The lead industry and public health officials instituted voluntary programs in 1955 to eliminate the use of lead in interior paints and reduce it in exterior paints.

Lawsuits against the Lead Industries Association and a 1978 decision by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission led to a complete ban, in residential housing, of paint containing more than 0.05 % lead by weight. Houses built before 1960 can remain a continuing respiratory hazard to residents, and abatement (permanent elimination of the lead hazard) may be required when a property changes hands. Young children in the US are the targeted cohort for monitoring the lead burden in the general population, and a recent lead threshold requiring remediation is 5 micrograms per deciliter of blood.

Similarly, white lead and lead acetate were used in cosmetics worldwide, but their use has stopped or diminished in the West. White lead itself was widely employed in cosmetics in the Roman Era, with white lead employed to lighten faces, overlain with patches of red lead to impart a rosy glow to the visage. White lead acquired added cachet in the 15th through 18th centuries, when it was routinely employed to create the dead white look, supplemented by vinegar skin peels and lead sulfate as a freckle remover. The popular use of white lead in cosmetics created a vicious cycle: skin so treated deteriorated, requiring the application of more cosmetics to conceal the ongoing damage. More than one aristocrat was said to have died a victim of cosmetics. By the late 19th century, the American Medical Association (1869) was campaigning against the use of toxic materials in cosmetics, and the Federal Government, through the Food & Drug Act of 1902, effectively ended the most dangerous chemical practices.

Lead acetate, a reaction product of PbO and acetic acid (CH3COOH, aka lead diacetate) is still used but regulated for cosmetic uses, and now limited to low-dosage applications as an incremental color additive for hair dye. It will darken hair over a period of days, requiring small applications on a weekly basis to maintain the color density achieved. Clinical testing has established the long-term safety of applications following the dosage recommendations; long-term accumulation of bloodstream lead has not been observed.

Occurrence of Cerussite

Cerussite occurrences are widespread and many are exceptional.

Europe

In England, clusters of delicate acicular crystals were discovered in the Pentire Glaze Mine, St Minver, Cornwall, The quantity of cerussite was large, and possessed a high lead content. Other productive sites were Weardale, in the Northern Pennines, Durham, and Frankmills Mine, Christow, Devon.

In Scotland, specimens were recovered at Leadhills, Lanarkshire. In France, the notable occurrence is from the Rossignol Vein, Chaillac, Indre. In Germany, the Friedrichssegen Mine, near Braubach, Rhineland-Pfalz is a cerussite locality, and Johanngeorgenstadt area of Saxony. In Italy, fine crystals came from Motevecchio, Monteponi and Iglesias, Sardinia.

In the Czech Republic, twinned crystals were common in Stříbro. Nice cerussite crystals came from Oloví and Příbram, and unusual needle-shaped crystals were found in Zlaté Hory.

Asia

In Russia, cerussite is found at Nerchinsk, Siberia. In Iran, the Nakhlak Mine in Esfahan Province is a good host.

Africa

In North Africa, two prime localities are the Touissit mine (noted for fine twins), and Mibladen, Morocco and Sidi-Amor-ben-Salem, Tunisia. Gray and yellow tinted cerussite crystals with galena and pink baryte from Mibladen are the most common cerussite specimens on the current market.

In Namibia, the Tsumeb District hosts superb crystals, v-shaped twin groups and intergrown snowflakes, as does the Kombat Cu-Pb-Ag Mine, 50 km south of Tsumeb. The complex snowflake shaped crystals from Tsumeb belong to the most valued cerussite specimens and can reach more then 10 cm in size.

Australia

In Australia, excellent cerussite specimens have come from Broken Hill, New South Wales; the Rum Jungle, Batchelor, Northern Territory; and at the Magnet and other mines, near Dundas, Tasmania.

North America

In the U.S., occurrences are recorded in several states: New Mexico, Arizona, Idaho, Colorado and Pennsylvania.

The New Mexico occurrences are best known from the Stevenson-Bennett Mine, in the Organ Mountains of Dona Ana County, and in the Magdalena District, Socorro County, where large, single cerussite and large twin crystals are typical.

The Arizona specimens are harvested from the Tiger Mine, Globe, Gila County; the 79 Mine in Hayden, Gila County; the Mammonth-St. Anthony Mine in Tiger, Pinal County; and Bisbee, Cochise County. Unique, fragile white crystals in spiky masses were found in the Flux Mine in Patagonia, Santa Cruz County.

In Idaho, crystal occurrences were found at the Kellogg, Monarch and Bunker Hill Mines, Coeur d'Alene, Shoshone County. In Colorado, the Lake County area is the site of numerous stratiform Pb-Zn deposits in the Leadville District. Finally, in Pennsylvania, cerussite was found decades ago in the Wheatley Mines of Phoenixville, Chester County.

Comments